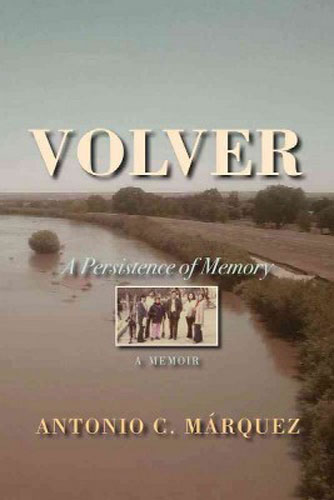

Volver

Antonio C. Márquez’s Volver is a “memoir” in the truest sense of the word, as its subtitle “A Persistence of Memory” suggests. Beginning in the Pre-World War II borderlands near El Paso, Texas, and moving to Los Angeles, the Midwest, and then all over the world, Volver recounts Márquez’s life and travels, from a poor boy to an established expert in his field who is called on by the government to be a cultural representative in other countries.

Antonio C. Márquez’s Volver is a “memoir” in the truest sense of the word, as its subtitle “A Persistence of Memory” suggests. Beginning in the Pre-World War II borderlands near El Paso, Texas, and moving to Los Angeles, the Midwest, and then all over the world, Volver recounts Márquez’s life and travels, from a poor boy to an established expert in his field who is called on by the government to be a cultural representative in other countries.

The selling point, and really the plot that drives the first half of the book, is that transformation. Márquez’s family is poor. They are frequent border crossers living on odd jobs as they can. Márquez escapes that life first by joining the Marines—though he never serves off the base, getting out just on the cusp of Vietnam—and then by going to college. However, what makes his retelling memorable is not the dramatic shifts in his life, of which there seem to be many, but the nonchalant, casual, and matter-of-fact way he presents his story.

The memories he presents are brief, crammed together, quickly moving from one to the next, hardly ever stopping to fill out a whole scene, as each memory feels almost detached and equally worth examining, but not too closely. This has the effect of making his life seem entirely ordinary, as though his dramatic shift in place and mentalities were just the natural progression of aging. Though Márquez certainly shows where choices were made and other options possible, this book does not dwell on possible pasts, but only on what actually happened, again creating a feeling of simply floating through his memories. He says he “was victim of the apocryphal curse: may you live in interesting times,” as though his life were a series of passive moves against him. And with the backdrop of the ‘60s & ‘70s as his most formative years, that seems like it could be true. But the story he tells goes beyond that: here is a man and his wife who made good choices, who sought to be more than the life they grew up with offered them.

That being said, the constant flow of memories is not always successful at engaging the reader or moving beyond simple recollection. One chapter is simply a list of places he and his wife (not often together) traveled, mostly in the service of their professional research. They move throughout Central and South America, Europe, and Asia. Like the rest of the book, the scenes, if there are any, are brief and move fluidly from one place to the next. However, here, as they were being dictated by government appointments and not the choices of youth, the action feels less personal, less reflective and more list-like. One might feel a little too quick to judge, wondering why Márquez is giving such a long list, but then, at the close of the chapter, he outs himself and justifies it. “The travelogue might seem smug and self-congratulatory, and someone might say, ‘Who cares about this claptrap, of where you went and what you ate?’ I claim its importance.” And the importance of all these exotic locations and foods and ideas? They are “markers of the distance—the distance, in space and time, from the penniless days. [ . . . ] We did it, against those odds, and it was no small matter.” This distance is not insignificant, and it is rather rewarding to read about, but the book, and perhaps just that chapter specifically, doesn’t feel quite complete because we have to be told the significance, almost like having to have a punchline explained. Were the stories and memories to essay more, or reflect more specifically and feel more intentionally collected, even the travelogue sections might have more distinctness and weight behind them.

But, for that same reason, the final chapter, which takes place largely in the present-tense, is the most impactful, the one that carries the most emotional weight, and is largely the most successful. In it, we learn that Márquez has suffered a fall, resulting in a head injury, and that he has compiled this book in the fear that his mind is failing. The collected pages are the memories that persist, which he admits have been hastily completed “cobbled [together with] autobiographical fragments and vignettes that [he] had written over the past ten years.” That the book feels hastily written is undeniable, but the knowledge of the gravitas behind the project allows a level of sympathy that brings out its better qualities and once again celebrates the main drive of the book: that, no matter our circumstance, we can move forward.