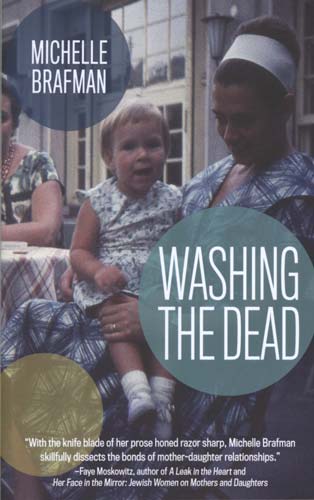

Washing the Dead

Intimate family relationships can startle us when we recognize that, despite our familiarity, we’re actually strangers who keep many secrets from one another. Such is the case for Barbara Pupnick Blumfield, who discovers as a teenage girl her mother’s infidelity. Author Michelle Brafman explores three generations of mother-daughter relationships in Orthodox and Chasidic Jewish families through the eyes of Barbara, contrasting her life in the 1970s when she first discovered her mother’s unfaithfulness, with her life as a grown woman in 2009, where she has a teen daughter of her own. Intimate family relationships can startle us when we recognize that, despite our familiarity, we’re actually strangers who keep many secrets from one another. Such is the case for Barbara Pupnick Blumfield, who discovers as a teenage girl her mother’s infidelity. Author Michelle Brafman explores three generations of mother-daughter relationships in Orthodox and Chasidic Jewish families through the eyes of Barbara, contrasting her life in the 1970s when she first discovered her mother’s unfaithfulness, with her life as a grown woman in 2009, where she has a teen daughter of her own.

Brafman does a good job of educating her non-Jewish readers on the ritual and religion of the Chasidic and Orthodox faiths. The story is liberally sprinkled with the language and terminology of the faith, though unfamiliar terms are smoothly defined, without the story feeling like a dictionary or primer.

Washing the Dead takes its name from the Jewish burial custom, considered the last great mitzvah (religious good deed) one can do for another. And yes, Barbara participates in this ritual as one of her many mitzvahs she performs throughout the story.

This is a story, however, of much more than modern-day life in the Jewish faith. It’s about the harm mothers can do to their daughters, and daughters can do to their mothers, both with and without intention. It’s about forgiveness of these wrongdoings, and about how faith can intersect both the right and the wrong of actions and emotions.

Barbara is a pensive, introspective, at times even depressing character who struggles with the guilt of keeping the secret of her mother’s infidelity with the shul’s (synagogue’s) Shabbos goy, a gentile assigned the duties that cannot be performed by an Orthodox Jew. When the clandestine relationship ends, Barbara’s mother June spirals into dark depression, and the vortex threatens to suck in the entire family.

When at last her mother’s extramarital affair is discovered, Barbara is certain her family will be excommunicated from the donated mansion that serves as the shul, but instead of her mother being sent away, it is Barbara who is sent across the country by the rebbetzin to live with a family in California.

Feeling unfairly exiled, Barbara works through her dark mood by escaping to the beach, at times alone in the dark of night. “I put my sneakers on, snuck out of the house, and walked. I walked and walked until my calves burned, three miles to La Jolla Shores in the dark and home again. If I kept moving, I could forget everything I’d left behind and distract myself from wanting it all back.”

It is not until her return trip home to attend her best friend’s wedding that Barbara realizes that being away from home might have been the rebbetzin’s own mitzvah for Barbara—the gift of freedom from caring for her mother. At first, Barbara is happy to see that her mother is now quite well; happy, even jovial, baking and cooking and attending to her household. But not even a full day of family bliss can pass before Barbara discovers the reason for her mother’s newfound joy: she’s returned to her affair with the Shabbos goy.

This time, Barbara leaves of her own accord to return to California, and as she does, she realizes the wisdom of the rebbetzin sending her away. “Maybe the rebbetzin hadn’t exiled me; maybe she knew that I needed to grow new skin.”

Though Barbara’s skin may be thicker, she still turns her thoughts and emotions inward, and it is this frequent—near constant—introspection that slows the story’s pacing to some extent. Barbara must now deal with her excitable teenage daughter Lili’s injury and subsequent surgery, which threatens to end the girl’s career as a prize-winning runner. Like mother, like daughter, Lili becomes sullen and quiet, and her silence affects Barbara’s peace more than her boisterous behavior ever could. As Barbara is dealing with her daughter’s prolonged recovery, she learns her mother June may be experiencing early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

It is the rebbetzin who unflinchingly charges Barbara with her mother’s care:

“She’ll need you.” The rebbetzin’s words bore the weight of Jewish law, halacha that demanded that I offer food, shelter, medical care, and exquisite, relentless respect to my mother and father. . . . I studied her face, searching her eyes for some trace of the hurt and humiliation my mother had caused her. They looked the same as always, full of purpose and principle. And love. She could put her old wounds aside for God and for me.

It is this example of forgiveness that weaves together the multi-layered plot of Brafman’s story. More family secrets come to light that change Barbara’s perception of her mother, endowing her with a newfound sense of compassion for not only her mother, but her daughter, her brother, and everyone else in her life.

Brafman does not take it easy on June Pupnick, Barbara Pupnick Blumfield, and Lili Blumfield: she puts her mother-and-daughter characters through the fire. Yet on the other side, each comes out refined, understanding that the legacy of one’s family requires understanding and true forgiveness, which may be the greatest mitzvah of all.