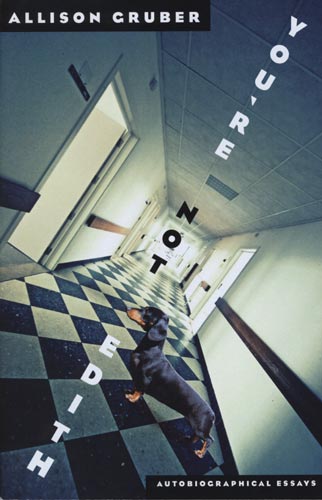

You’re Not Edith

Allison Gruber’s You’re Not Edith is one of the better books I’ve read this year. Her “autobiographical essays” are funny without being comic, personal without being egotistical, crude (because she describes teenage life and dog vomit) without stepping into vulgarity, showing a narrator who is lonely but not melodramatic, tender without becoming sentimental. I read the whole book in one short, luxurious morning, and found that the end came too soon. That the last essay tells the story of a fan who flirts with her after a reading is totally understandable: to read Allison Gruber is to want to read more and to get to know her better. Allison Gruber’s You’re Not Edith is one of the better books I’ve read this year. Her “autobiographical essays” are funny without being comic, personal without being egotistical, crude (because she describes teenage life and dog vomit) without stepping into vulgarity, showing a narrator who is lonely but not melodramatic, tender without becoming sentimental. I read the whole book in one short, luxurious morning, and found that the end came too soon. That the last essay tells the story of a fan who flirts with her after a reading is totally understandable: to read Allison Gruber is to want to read more and to get to know her better.

Of Montaigne, Alexander Smith said “He tells us everything about himself, we think; and when all I told, it is astonishing how little we really know.” And though Gruber’s essays are perhaps more narrative than montaignian, more focused on story than lyric, this statement is true for her. Like the best essayists, we are brought into her confidence, we get the “funny stories, odd stories” which only her trusted friends get, so that we are brought into the inner world of her obsession with Dian Fossey, her father’s mental illness, and her breast cancer treatments. In all of these, we get the multifaceted face of the essayist, who on one hand wants to tell us all, but who in public is reserved, eccentric, and private.

This delightful duality of private and public is especially well-displayed in the last (and best) essay of the book “Speaking to Strangers.” This essay braids about her massage therapist, Maeve, who is working with her after a breast cancer surgery; the Fan, who flirts with her after a reading and ends up spending the whole day with her, but to whom she never tells about the cancer; and other strangers—especially nurses and cancer survivors. In the essay, the Fan spends all day with Gruber after a reading, suggesting one activity after another, obviously flirting with her, wanting a more intimate relationship. But the Fan is never told about the breast cancer or the upcoming chemo treatments, or that her dog is also sick, and though the subject of Gruber’s inexperience with the city of Milwaukee, where Gruber was a new resident, comes up repeatedly, she never mentions that the inexperience is because she is too sick to explore. But we the readers do get all of that information through the narrator’s asides and through her conversations with Maeve, the honey-eyed therapist who seems to be sympathetic in all things, and who does refer to Gruber as a friend once when they chance to meet in public, but who is, ultimately, not an intimate. All these stories are paired, heartbreakingly, with the story of the author’s long-time friend Emily who announces that she can’t deal with Gruber’s cancer, and so never calls her again.

These complications are common in life, but Gruber creates an uncommon delight in describing them. For example, in “Music in the Head,” an essay about her father’s mental illness—which also ebbs and flows with his obsession for music—Gruber mentions in an aside that she had a complicated relationship with Tipper Gore, who in the same administration, successfully lobbied for parental warnings on music lyrics and for the rights of people with mental illness. So while the parental labels meant her mother denied her the “seriously good rock music,” Ms. Gore’s work with the mentally ill also meant Gruber “grew to have tremendously conflicted feelings about Tipper Gore.” The attention to these small moments, small eccentricities and oddities, makes the whole book a delight, with new surprises and insights from page to page.

While some of the marketing for this book might suggest it is a story about a cancer survivor or about a lesbian, that emphasis does the book a disservice, since it is not exactly her sexuality or her health that are in question, even though they are discussed some. Rather, it is a human book, about a person and the quirks of that personality. To paraphrase Alexander Smith again: “If a person is worth knowing at all, they are worth knowing well.” Through Allison Gruber’s ten delightful essays, we get to know her and a wide cast of friends and family well because she takes the time to give us her thoughts, her stories, her private moments, making it a book well worth the read.