Big Fiction – Summer/Fall 2014

Only two stories—but two big stories, longer than short stories and shorter than novels, big in word count and big in quality—is what this beautiful issue of Big Fiction offers. When you read the website, you think: big ambition! When you hold the book, you think: big, admirable taste in design and material! When you dive into the stories you think: big winners! big pleasure! big success! This issue is, to put it in big letters, EXCELLENT. SPECTACULAR. WELL WORTH YOUR TIME. Only two stories—but two big stories, longer than short stories and shorter than novels, big in word count and big in quality—is what this beautiful issue of Big Fiction offers. When you read the website, you think: big ambition! When you hold the book, you think: big, admirable taste in design and material! When you dive into the stories you think: big winners! big pleasure! big success! This issue is, to put it in big letters, EXCELLENT. SPECTACULAR. WELL WORTH YOUR TIME.

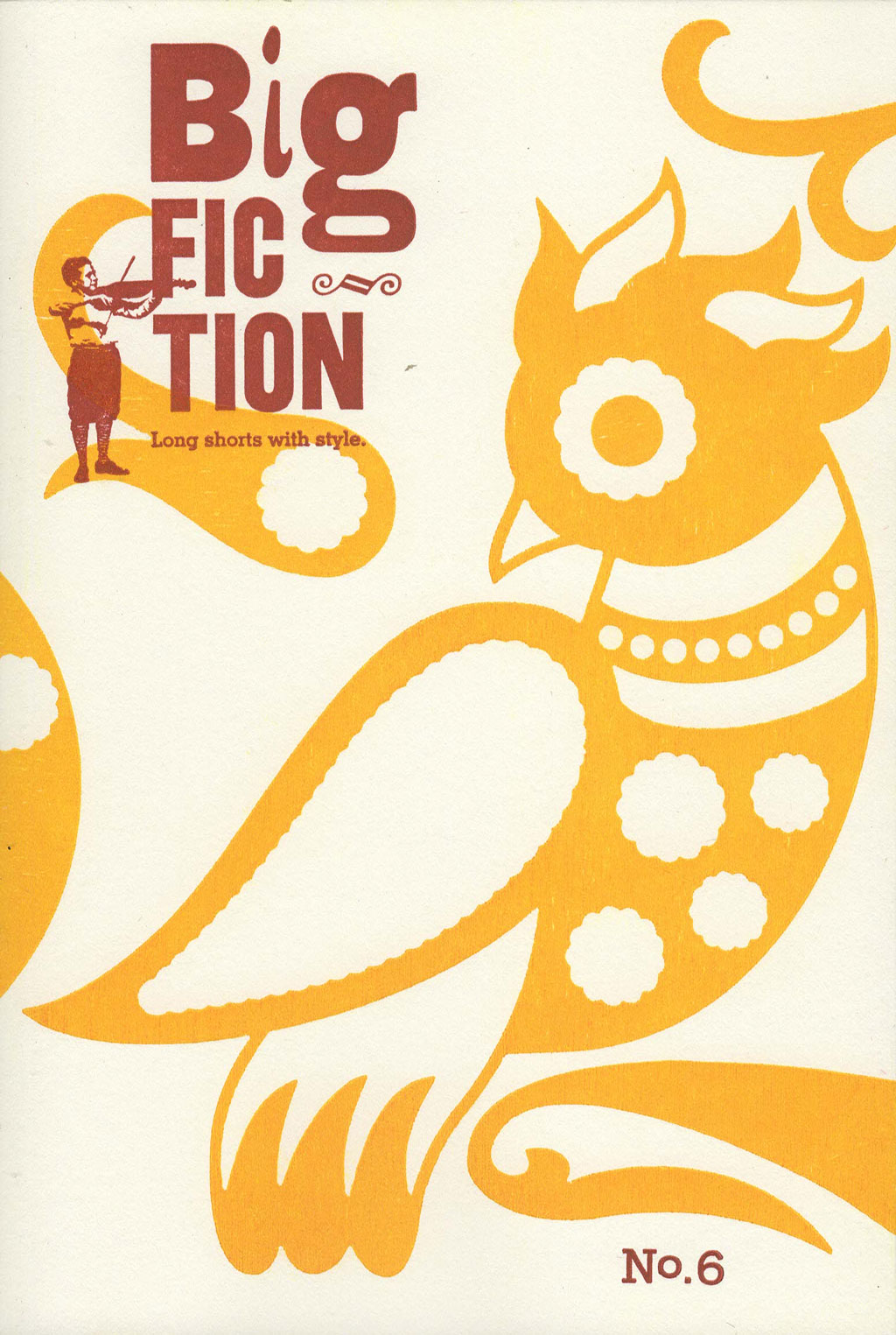

The first thing you notice with Big Fiction is the visual and tactile attractiveness of the cover. Illustrated by Tory Franklin and hand set by Bremelo Press, it’s about 5 x 8”, with lots of white space, a curlicue yellow Maya-bird, and, up in the left corner in maroon, the unobtrusive logo: the title with the little boy playing the violin. You run your fingers over it and feel the feathers and dots, the letters (some big, some little), the clarity of the unclaimed areas. The volume is easy to hold—you can take it with you on a walk, if you like (I do), or hold it while you’re riding the exercise bike or stirring the oatmeal. Which is a nice thing, because once you start either of the two big stories, you don’t want to stop.

This is the Knickerbocker Prize issue. It was judged this year by David James Poissant, of the University of Central Florida, author of numerous stories and one collection, winner of many awards, and advocate of terrific fiction, as his enthusiastic headnote to the issue makes clear. It’s tempting to quote in full his paragraph describing the two stories, but if I did, the review would be finished, and I want to add my own effusions. Suffice it to say, his words were as fun to read as the Knickerbocker Prizewinners themselves. I was glad to have been introduced to the stories so enjoyably. Good judges must pick good stories . . . so . . .

The winner, Alan Sincic, of Orange County School of the Arts and Valencia College in Orlando, Florida, gives us “The Babe,” perfect reading material for the weeks of the World Series (and a local community theater’s production of “Damn Yankees,” too—I felt utterly immersed in baseball). He dies. That’s the first line, so I’m not spoiling anything: Babe Ruth dies. What happens in the next 61 pages takes us only to the end of the day, but it takes us everywhere in baseball, in competition, in love, in language, the most fluid flowing catch and pitch of wordage and outage (or not) you can imagine. Two sentences, just to reel you in:

So much for the bubble that held the game. But then he looked back at the break in the fence and saw that it was perfect: a breach in the boundary of the game just big enough to contain not only the Babe but also the ball there bounding down the cobbled streets of the Bronx, the ball spinning into and out of the broken sunlight to spank the hood of the roadster, to rainbow up over the boaters and the derbies and the bonnets, to nip the tip of the stogie and ping the arm of the hydrant and hop the stoop and shatter the window and clatter the spoons and splatter the pans in a rebound, in a ricochet, in a bank shot to the bedroom where the widow would be waiting, all crispy and frisky and fried . . .

You get the idea, right? What happens to the ball if the Babe dies? This is what happens—Alan Sincic takes you from the windup to the final call on Home Run 715, and you can hardly stop to breathe.

It’s terrific.

The second place winner, Margaret Luongo’s “Three Portraits of Elaine Shapiro,” has equally perfect pitch, but it’s a very different story. Three “portraits” emerge in three sections, each a self-contained world, though one of the miracles of the piece is that all of them take place in New York City and involve the interior world of the recognizably same person. Yet each is its own “spot of time,” with varying supporting cast, reminding us that our lives are like that too: what happened when we were twenty-two happened to a different person than the one to whom things happened at thirty-one and forty-two. In Elaine’s case, as in ours, what happens at twenty-two shapes what happens later, and, like us, at forty-two, she claims the present self with both fierce possessiveness and inevitable regret. We make the decisions we do at the time—and then we live with them. Luongo’s style is clean, low-pitched, steady, and sympathetic. This issue would make a wonderful gift for anyone who loves to read. Buy it. Subscribe. Submit.

[www.bigfictionmagazine.com]