BULL – 2015

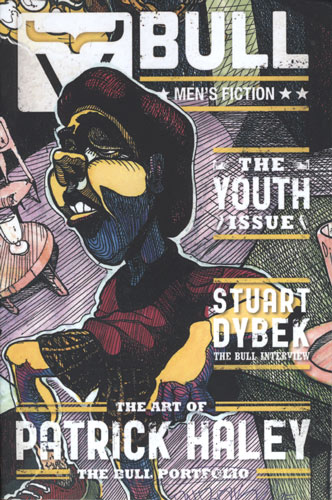

BULL Number 5 is covered in colorful, urban-styled art, created by the late Patrick Haley, whose work is profiled at length in this issue. Inside, his black and white drawings of surreal settings, strange creatures, and highly-detailed settings take influences from a variety of interesting visual sources such as Salvador Dali, R. Crumb, Heavy Metal magazine, and street graffiti. Each of the thirteen pages of drawings and sketches plucked from the artist’s notebooks tells a story, even the most basic “practice” sketches, with a couple in particular that could make one feel as though they could fall right into the page. BULL Number 5 is covered in colorful, urban-styled art, created by the late Patrick Haley, whose work is profiled at length in this issue. Inside, his black and white drawings of surreal settings, strange creatures, and highly-detailed settings take influences from a variety of interesting visual sources such as Salvador Dali, R. Crumb, Heavy Metal magazine, and street graffiti. Each of the thirteen pages of drawings and sketches plucked from the artist’s notebooks tells a story, even the most basic “practice” sketches, with a couple in particular that could make one feel as though they could fall right into the page.

There is much more than visual art within these pages. The editors look for anything that furthers the discussion of modern masculinity and accepts submissions from any and all backgrounds to perpetuate that dialogue. The theme of this issue is “Youth,” and every fiction piece explores that theme with clarity and a solid understanding of what makes a compelling story. The issue is bookended by what I think are two of the best selections offered here, Joey R. Poole’s “I Have Always Been Here Before” and Rod Siino’s “Frankie Would Be Almost Nine.” The former story is a quirky tale of an abandoned infant, a mysterious detective who takes up shop in a trailer park, and a cockroach-eating contest with a large snake as a reward. The characters could find themselves right at home in an indie film with a substantial comedic trash factor, a la Raising Arizona. Siino’s story is more of a serious “you can’t go home again” exploration of a thirtysomething struggling with childhood memories after returning to his hometown to handle his deceased mother’s personal affairs, all while risking a profitable business deal back home that his girlfriend has to help with.

Jarrett Haley (brother of the cover artist) offers the teenage tale “Pink Elephants in Oldsmar,” as the characters attempt to work their way through their awkwardness towards friends and the opposite sex, while drifting down a river to a local secretive attraction. Sexual tension, observations of different economic classes, and the ever-constant threat of getting caught by parents are all at play here, told with slight nostalgia and an almost reverent tone when describing his older brother and his exploits, providing evidence of this story hitting Haley close to home.

The BULL Interview is with Stuart Dybek, a writer, poet, and longtime English professor at Western Michigan University. Dybek briefly discusses humanity’s infatuation with youth and the reasons for the prevalence of coming-of-age tales in fiction (with the answer having to do with the universality of aging, a process everyone can relate to). He names a few lesser-known foreign and American writers he admires and takes a look back at his own childhood on the south side of Chicago. He also offers advice to young writers, telling them to approach the craft of writing as though trying to learn how to play the piano, i.e. learning many aspects of the craft as a filmmaker or musician would.

“The Jackpine Savage” by Josh Amidon tells the story of a young man visiting the places where his lumberjack father worked, played, and slept, emulating his father’s actions in an attempt to learn more about him and his life. He rubs elbows with the same hardscrabble laborers his father spent time with, as he tries to piece together his father’s time spent there from tales the protagonist hears and suspects may be as tall as the trees they saw into. But the young man soon realizes that even though he ended up thousands of miles away, his roots remain in that dying backwoods town like ghosts that cannot be exorcised.

Although BULL carries the subtitle “Men’s Fiction,” there is nothing within these pages that pretty much any reader couldn’t relate to in one way or another. As Dybeck states in his interview, we all grow and age (if we’re lucky) and the characters within stumble toward the future as blindly as everyone else, trying to find and accept a solid, meaningful link that ties the past to the present. Many of these stories carry a universal appeal not only geared toward male interests. There are no stereotypically masculine stories of bullfights, battlefields, or fathers and sons bonding over a fresh kill in the forest. If anything, the men within these pages have complicated relationships with their fathers (if any at all); their various paths taken in a changing world are in the spotlight as they hurtle into uncertain futures. BULL hones its strengths into fine points of compelling, narrative fiction that readers of many backgrounds should enjoy.

[www.bullmensfiction.com]