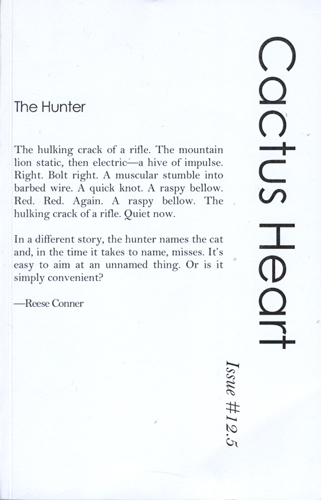

Cactus Heart – June 2015

Cactus Heart is one wicked lit mag. With a spiny cactus bursting out of a skeleton ribcage as their logo, don’t go searching these pages for the soft and sentimental. No box of Kleenex needed here. Instead, be ready to steel yourself against hard truths, take a moment’s pause to settle quietly brutal characters into your imagination, and shift world views subtly through the surreal and abruptly through the confessional. Cactus Heart is one wicked lit mag. With a spiny cactus bursting out of a skeleton ribcage as their logo, don’t go searching these pages for the soft and sentimental. No box of Kleenex needed here. Instead, be ready to steel yourself against hard truths, take a moment’s pause to settle quietly brutal characters into your imagination, and shift world views subtly through the surreal and abruptly through the confessional.

Marcona, the socially awkward but ‘brilliant’ high school character in Renée Thompson’s story “Brilliance” is introduced by the narrator in the first line: “She had cut her wrist with a knife and bled all over her dog.” Brutal, yet this fact gets lost as the narrator continues describing Marcona’s “genius” as well as “oddity” so that by the end, as she stands “holding a dog, a little Chihuahua, tightly to her chest,” it comes as a surprise that it runs away, “covered in blood.” Marcona is terrifying, but in the sense that you can’t turn away from her; Thompson’s detailed character of genius/curiosity keeps readers looking.

Bernard Grant’s story “Rusty and Lulu” creates an uncomfortable parallel between the behaviors of dogs and that of humans, forcing us to see the hard truth of our animal selves. As in Sarah Sorensen’s “Feral Cats of Kalamazoo,” where the cats in the story are actually domesticated. It’s the humans whose emotions have gone wild: Kaitlyn self-centeredly obsessing in a drunken stupor about her ex, Elena; the taco delivery guy whose own life issues deplete any empathy he might have for others.

It’s worth noting that there are several pieces in this issue with queer subjects. As an old lady who won’t be in the generation to grow up with easy access to LGBTQIA literature, I deeply appreciate being able to witness this transition in our culture, and appreciate publications like Cactus Heart that contribute to the normalization of this (no special issue, no pronouncement of a special feature—it’s just THERE).

In some, it’s obvious, such as the poem “What a Padded Camisole Said to Me” by Shawntai Genell Brown, that addresses both orientation and cultural heritage. “Do I have the black woman shape?” the narrator asks as her Auntie dresses her in a padded camisole. The narrator notes that “Before I loved women / who learned to love what makes a woman” she looked at her body with a different critical eye, “butt flat as wall siding in a vacant house / not enough insulation to pass inspection.” Though by the poem’s end, she reveals her accepted truth in this subtle smack down:

“You’ve got to show him what you’re working with,”

Auntie says.

But I’m glad I didn’t come with much

or

look for much

to add to it.

“Emotional Refrigerator” by Nick Hadikwa Mwaluko is perhaps less obvious, though starting abruptly:

They raped me. I don’t know who or

how many. I stopped counting the number of

times. All I remember is praying. I don’t

remember to who. But I wanted to survive. To live[.]

The narrator turns to a God, a Higher Power, comes to a safe place, and buys a penis that is “big, it is dark, it is African like me” and will be worn “like a woman. She cannot hurt / anyone.” The poem stands as a barbed and beautiful testimony to survival, but is strengthened in meaning and testament of queer literature knowing Mwaluko is “an FtM masculine-identified American born in Tanzania and raised mostly in Kenya plus other African countries.”

On the open-to-interpretation queer was the poem “Varsity” by Baylea Jones, where, if the author’s gender isn’t revealed to be identified with the narrator, then the characters in the poem could be read as straight or gay, male or female. The line “Now you’re hoping I don’t see you, hiding the glinting ring between your white knuckled fingers” can be run through multiple interpretations of the relationship between the two characters, of the impact of this reveal on the cultural expectations of gender norms in our society, and more. A rich poem I would love to have the opportunity to explore with a class of students or a readers’ circle.

The two nonfiction pieces are worth mention for the impact of their subject matter: Sam Tabet’s “Ghosts of Beruit,” about a son comforting his father’s night terrors, “. . . I imagine you as a young boy—M16 in hand, watching your friends die around you like domino pieces, one after another, their bodies not yet fully formed.” And Megan Amanda Taylor’s “Galilee,” in which she explores multiple boundaries of culture, expectation, gender, and the intersectionality of those:

When the newspaper reports around 1,000 Pakistani women killed yearly by their families in “honor killings.” When the history books say approximately 9,000 women burned as witches in Salem. What is the exact number? It makes a difference. Rounding numbers is an act of war, leaving individuals out of the count, forgotten. Round. The numbers are too sharp for us.

Cactus Heart is a publication of impact. There’s not a piece in here that didn’t leave me reeling, contemplating, dredging the depth of some adverse emotion that needs to be felt to understand the plight of others. I never would have put cactus and heart together, but having read this publication, it now seems absolutely appropriate for reflecting the literary sensibilities within.

[www.cactusheartpress.com]