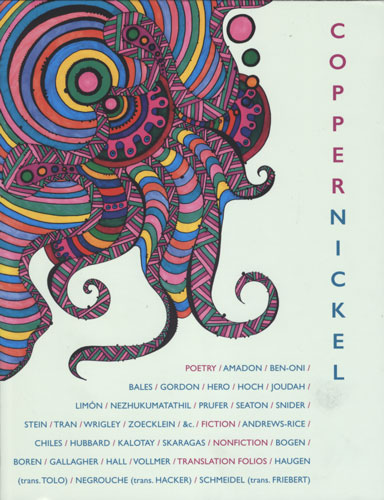

Copper Nickel – Spring 2018

Unlike the vast majority of literary and popular magazines, Copper Nickel does not greet their readers with an editor’s note outlining the materials of the issue. They do not offer a lens for readers to examine featured pieces. And why should they? The featured works of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and translation folios speak for themselves; they do not require an approach or an explanation. What the editors do achieve, however, is to provide the magazine’s readers with the freedom to imagine and interpret authors’ works without any imposed limitations. Plus, let’s be honest, no one buys magazines for their editor’s notes; we buy them for art, and in the Spring 2018 issue, art speaks for itself.

Unlike the vast majority of literary and popular magazines, Copper Nickel does not greet their readers with an editor’s note outlining the materials of the issue. They do not offer a lens for readers to examine featured pieces. And why should they? The featured works of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and translation folios speak for themselves; they do not require an approach or an explanation. What the editors do achieve, however, is to provide the magazine’s readers with the freedom to imagine and interpret authors’ works without any imposed limitations. Plus, let’s be honest, no one buys magazines for their editor’s notes; we buy them for art, and in the Spring 2018 issue, art speaks for itself.

When first opening this issue, I was immediately taken with Kevin Prufer’s poem “The Art of Fiction.” The image of an old lady, who lost the poetry contest, chiding the speaker is still imprinted in the back of my mind:

Later, in the parking lot,

a woman I’d then have called

very old told me,

Someday

you’ll understand how your poem has hurt me;

I don’t expect you to get it now, but

Someday.

While the image of a bitter old lady may seem humorous at first, the poet quickly changes the tone of the piece. He masterfully intertwines the themes of mortality, the arbitrary quality of language, and a number of serious issues of our contemporary society. Chilling and insightful, “The Art of Fiction” remained my favorite poem of the issue even after finishing the entire magazine.

Emily Chiles’s fiction piece titled “Mother Animal” also explores the idea of stories, or fiction, determining reality. Driving to their farm market, a married couple notices the dead bear on a side of the road:

What first came into view as they crested a hill was the curve of the embankment, a wild tangle of trees and vines that sloped towards the road. At the edge of that tangle was the black form, the paws sticking up, the snout aimed at the sky. At first, she thought it was just a thick, gnarled branch jutting from the undergrowth. Then, she thought, maybe a jumble of tire scraps hemorrhaged from a passing semi, or a bag of trash, or a pile of burned wood. People abandon all kinds of things on the side of the road: mattresses, mateless shoes, rusty lawn chairs.

But then the man said, “God. That’s a bear.”

The couple drives by and goes on about their day, burdened by their own problems. Later, the wife drives on the same road and speculates about what has happened to the dead bear. At this point, Chiles leaves her readers with a few options; each and every one of them creates ambiguity while suspiciously hinting at possible truths.

In nonfiction, Sari Boren’s essay titled “The Slurry Wall” also explores the abilities of language in a way: for some, it can be a security blanket, for others, it can create a deep, symbolic meaning. Boren, a museum exhibit developer, takes her readers to the 9/11 Memorial Museum. The focus of the essay is the slurry wall of the Trade Center. Boren writes:

I love the sound of slurry wall, full and round in the mouth, how the term, like the bathtub, is a contradiction; slurry is made from particles of pulverized solids (clay, coal, or even manure) suspended in liquid (usually water). Slurry wall sounds like something it’s not.

The author explores the relation between the slurry wall and democracy that was originally tied together by an architect, Daniel Libeskind. In addition to this brilliant exploration, this essay is written in an ironic, lively tone making it one of my favorite nonfiction pieces so far.

I cannot finish this review without mentioning Maureen Seaton’s poem “James Franco.” Who says poetry has to be about “high” and “poetic” subjects? Why not a movie star? James Franco becomes a kind of mirror for the speaker:

James Franco is both straight and/or gay, like me.

He humanizes his life in much the same way I do,

stripping off his skin, cracking open his famous skulland rearranging his brain in couplets and quatrains.

James Franco—what an unusual subject to write about! The poet takes her piece from this “poetic” pedestal down to pop-culture and Hollywood stars, yet it still has something deep and meaningful to offer. Seaton explores the idea of discovery of the self through others. I absolutely loved this poem.

In addition to fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, the twenty-sixth issue of Copper Nickel features what they call translation folios. One of the folios offers excerpts from Paal-Helge Haugen’s long poem, or “a bullet-pointed novel.” In this work, the Norwegian writer not only “explore[s] religious texts” but also creates an experimental and collaborative work that involves both the reader and author. Disruptive, rich in detail, and intimate, these translations seem to be jewels handed to the English-speaking audiences by Julia Johanne Tolo.

Inside the pages of the Spring 2018 issue of Copper Nickel, I found myself lost. It was not because of difficulty understanding or following the pieces, but because it was easy to lose myself in the diverse voices brought to me through art. From faraway places like Norwegian woods to familiar places like in front of the computer screen, the prose and poetry have offered me a freedom to imagine and reimagine new and old worlds.

[copper-nickel.org]