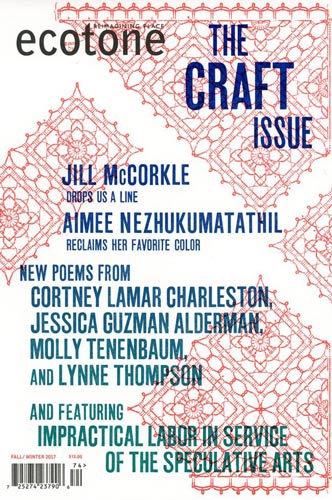

Ecotone – Fall/Winter 2017

For an issue on craft, let’s start at the end where it all comes together. Ecotone, a journal of place, concludes with contributors offering a single sentence on what craft means to them. Contributor Emily Larned says, “Craft shows us how to live: deliberately, conscientiously, mindfully, and as well as we possibly can.” Ecotone publishes authors and artists whose words are deliberate, whose language and choices are mindful and precise in communication.

For an issue on craft, let’s start at the end where it all comes together. Ecotone, a journal of place, concludes with contributors offering a single sentence on what craft means to them. Contributor Emily Larned says, “Craft shows us how to live: deliberately, conscientiously, mindfully, and as well as we possibly can.” Ecotone publishes authors and artists whose words are deliberate, whose language and choices are mindful and precise in communication.

Jill McCorkle’s short story “The Lineman” is literally about communication. The narrator, Ricky, is an old-school handyman who fixes telephone wires. But while he understands wired communication, modern social interaction boggles him: his second marriage is falling apart, and he has no idea how to connect with his teenage daughter. He communicates with the reader instead, a plea that we will understand. And yet, McCorkle opens the story as if Ricky knows we will not comprehend, despite his best efforts: “I am a lineman for the county. It’s true.” He tells his story in short anecdotal bursts as if each piece is a new attempt for us to see his perspective and say I understand.

“Foreigners” by Farah Ali is one-sided communication told through direct address. The American narrator lives in Pakistan and it is his job to interview visa applicants to the USA. Ali tells the entire piece as the narrator’s monologue because he does not really hear the answers of the married couple he interviews. He paraphrases their words back to them—and therefore to us—skipping their choice of words entirely. Noting that the couple has been to the United States once before, the narrator asks, “Why on earth would you want to visit the same place twice? You say it’s to see your daughter, whom you love dearly. Why is that? No, not why you love her.” Ali’s greatest skill in crafting this piece is the way the narrator reveals so much about himself and his homesickness: “did you and others like you congregate like lost birds?” he asks the couple, “Did the aching muscle in your tongue relax as it stretched itself into familiar words?” Ali never lets us forget that he is a foreigner in Pakistan, all but shouting anger and frustration.

Andrea Mummert Puccini looks at precision and communication through the physical craft of crocheting in her essay “Snowflake No. 1.” Puccini plans to crochet snowflakes to give away as gifts, the way her own late-mother once did. But Puccini never learned to crochet. To convey her confusion and frustration at her lack of skill, Puccini’s language is full of miscommunications. She sends letters to her mother’s childhood friend but finds she does not understand the woman’s intentions in the written response: “I couldn’t tell if she wanted to give me a vote of confidence, or let me know I wasn’t obliged [ . . . ] or if she preferred not to be asked.” This same miscommunication occurs when Puccini provides an excerpt from the crochet pattern: “Ch 6; join with slip st to form a ring. / Rnd 1: Ch 4,” and on and on. This is not a language she speaks, and she can only call it “inscrutable code.” Puccini uses her language to convey the craft (of crocheting and letter writing) as literal communication and miscommunication.

Cortney Lamar Charleston’s poem “(Sub)Urban Dictionary” focuses on the narrator’s experience communicating his black identity and language while growing up in the suburbs. He merges his personal experience with his word choice as his poem takes on the form of dictionary entries: “J-A-W-N. Entry, dated 2003: a person, place, or thing. [ . . . ] I’ve been a person, a place, / a thing.” Charleston chooses a similar dictionary style as he explains multiple definitions of the more common word murder. As he lists these definitions, he shows the burden of being the one forced to explain, forced to communicate in limited white speech. Charleston’s poem is thankfully not limited. He is “tearing through the meat of grammar with my teeth / fools got me tweakin’ off this ghetto glossary gimmick fo’ real.” He is precise in his use of slang as well as his use of the dictionary form.

In the Letter from the Editor, Ecotone is named as a “teaching magazine.” No wonder then, that finishing this craft issue feels like you’ve gained a new skill, like you’ve gotten more attuned to your craft, like you have the ability to be more mindful, more precise in your communication.

[ecotonemagazine.org]