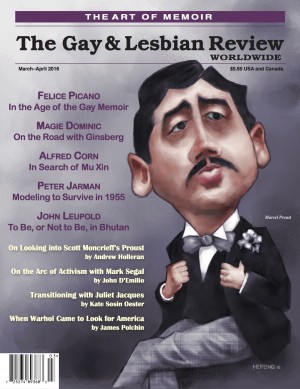

The Gay & Lesbian Review – March/April 2016

The Gay and Lesbian Review (G&LR) analyzes and affirms queer culture in the arts. The March-April 2016 issue, The Art of Memoir, compiles essays, book and theatre reviews, and a smattering of poetry to comment on and question how far the queer movement has come (or hasn’t). The Gay and Lesbian Review (G&LR) analyzes and affirms queer culture in the arts. The March-April 2016 issue, The Art of Memoir, compiles essays, book and theatre reviews, and a smattering of poetry to comment on and question how far the queer movement has come (or hasn’t).

Randy Blazak’s “How David Bowie Bent My Gender” uses his experience as a Bowie fan to comment on gender and positive queer role models. To Blazak, Bowie represented queerness. Bowie was “an avatar of our awkward young selves as gangly beings who had just fallen to earth, genderless, omnisexual.” Blazak invites the reader to share his experience, as our experience. Our lives are touched by Bowie’s music and his death. Blazak’s essay is sentimental without melodrama and affirms a history of misfits and queer identities.

The G&LR mainly focuses on the G and L of LGBTQ, but occasionally remembers the rest of the queer alphabet. Kate Sosin Oeser reviews Trans: A Memoir by Juliet Jacques. Oeser’s writing is direct, if not a bit academic, and I knew from the start why this book mattered. “Trans broadens the growing genre of trans literature [ . . . ] as a means of achieving personal congruity rather than ostensible womanhood.” By the end of the review, I knew what to expect of the book’s flaws. Oeser’s review is a useful critique as well as an acceptance of trans identity under the queer umbrella.

Alfred Corn’s essay “In Search of the Spirit of Mu Xin,” however, meanders without purpose. Corn introduces Mu Xin (1927-2011), gay Chinese visual artist and writer. But while Mu Xin’s biography is fascinating, and the inclusion of a queer person of color is a wonderful step, Corn’s intention behind the piece is unclear. He leads us through his invitation to a museum gala in China celebrating Mu Xin’s art, but then tells us more about the architecture than Mu Xin’s work. Maybe Corn is commenting on Chinese gay culture, but all he says is that “As matters now stand, [China] does not seem to have any noticeable gay activism.” Did Corn intend to discuss Mu Xin’s queer life? Mu Xin’s art? Queerness in China? He concludes without any answers or direction.

From start to finish Margaret Cruikshank’s review of Same-Sex Marriage, Context, and Lesbian Identity: Wedded but Not Always a Wife by Julie Whitlow and Patricia Ould holds its point. Same-Sex Marriage compiles interviews from lesbians of diverse backgrounds, asking why they got married and how they refer to their spouse. Cruikshank understands that the book seeks to unpack language usage among lesbians. She breaks down the authors’ arguments so we understand the power of language and context: “Whitlow and Ould make the important point that context and situation often determine what language lesbians use to describe themselves. They may feel safe with ‘wife’ in some situations but not in others.” By incorporating safety, we know what is at stake. Cruikshank then asks questions alongside her critique. Can lesbian culture continue to be radical in the conservative bonds of marriage? Will same-sex marriage “change gay and lesbian life itself?” Cruikshank does not provide an answer, nor should we expect one.

The G&LR displays gay culture in celebrity life, literature, and theatre. It’s a place to trace how far queer life has danced out of the closet and what this new normal could mean. The G&LR is not the most inclusive or diverse queer publication. And yet, the authors invite us to experience queerness, celebrate and critique queerness in the arts, and raise the most difficult question: What’s next?

[www.glreview.org]