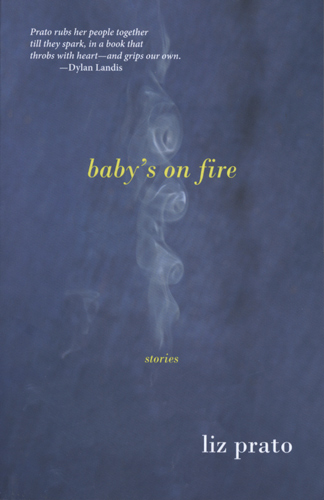

Baby’s on Fire

Running beneath each story in Liz Prato’s collection, Baby’s on Fire, is a murmuring chaos, the kind that seems to bubble beneath the surface either as the aftermath of or building up to a full-blown eruption. But those eruptions never come to readers in the span of the narratives. They’ve already happened, or this story is the building up to it, or it may never happen at all, and what we witness in these lives is precisely what we witness in the lives of people who surround us on a daily basis. Whole lives lived, the full details of which we have absolutely no awareness, but that simmer there, just below the surface. Just like our own lives in relation to others. Running beneath each story in Liz Prato’s collection, Baby’s on Fire, is a murmuring chaos, the kind that seems to bubble beneath the surface either as the aftermath of or building up to a full-blown eruption. But those eruptions never come to readers in the span of the narratives. They’ve already happened, or this story is the building up to it, or it may never happen at all, and what we witness in these lives is precisely what we witness in the lives of people who surround us on a daily basis. Whole lives lived, the full details of which we have absolutely no awareness, but that simmer there, just below the surface. Just like our own lives in relation to others.

Lives in relation to others is a key theme in Prato’s collection. The opening story “Baby’s on Fire” brings jobless college graduate, Jude, back to live with her mom and brother, Spencer. Prato’s signature style is in revealing the story slowly, not just to us, but to the characters in the narrative. This is no simple feat in the form of a short story, but the manner in which she discloses information, shares subtle details, and pulls in backstory is adept. As Jude gets picked up at the airport, she notices her mom “wearing a tie-dyed dress that hung on her like a parachute.” Since the setting is Portland, this detail didn’t have much impact on my perception of it until a moment later, Jude thinks, “She was wearing running shoes with that stupid dress.” And finally asks, “What’s with the dress?”“My dress?” Mom looked down, but not like she forgot what she was wearing. Like she forgot she had clothes on at all.

“Yeah, it’s too big for you. And kinda ugly.”

“Nice to have you home,” Spencer said. “Already a pleasure.”

“Well, it is. And why are you wearing your running shoes?” I looked back at Spencer. “I mean, that’s weird, right?”

“Mom!” Spencer’s voice cracked like he was thirteen. “Say something.”

“Honey.” Mom reached across the emergency brake and held my hand. “I don’t know how to tell you this.”

“Tell me what?”

“There was a fire,” she said. “It burned down the house. There’s nothing left.”

This dialogue exchange is also typical in Prato’s writing—natural conversation and repartee. And I don’t think telling about the fire is the big reveal in this story so much as the relationship between Jude and her cousin, Jimmy—with intimacies not actually illegal in Washington, unless the two wanted to get married. Okay, so I gave that away, too, but for good reason.

My first inclination was this was not the story to start this collection. Not just for the cousin sex thing, (which might be enough to cause some people to put the book down, and that would be a damn shame), but because I don’t think it was necessarily the strongest story in the bunch to bring in a wide audience. It does exemplify another of Prato’s strengths: developing characters we are okay knowing about, but don’t really want to get too close to. We all know people like these characters, and no doubt, we are one of these people ourselves to someone in our lives.

And in fact, there is nothing terribly endearing about any of Prato’s characters. In “The Adventures of a Maya Queen,” Laurie decides to part ways with Peter while on a trip to ancient ruins in Guatamala (do they ‘break up’ or not—it’s left a bit ambiguous). In “Cool Dry Ice,” Caroline, on a layover in Denver, meets up with her friend Kort, recently dumped, who suggests they try becoming more than friends. And in “Riding to the Shore,” Ginny’s daughter Christy comes to visit, further along in Ginny’s cancer treatments than her partner Deb finds acceptable behavior from a should-be loving daughter, but Christy’s struggle to accept her mother’s lesbian partner seems culprit in the cause.

Twelve stories in all, each story as divergent from the others in character, setting, and situation. Yet, I found the ‘arm’s length’ approach captivating in Prato’s work. I want to get into a character, to take a side, to feel that strong urge of being for something in the stories, but it just never quite happens. Something shifts in each narrative making it uncomfortable to get too close. I hate cliché, but isn’t that life? Aren’t our lives all just a bit messy, yet we still yearn to belong, to be understood, to be normal, to be loved? We try for that, but also live and make choices every day that keep the chaos roiling just beneath the surface, just enough to keep some people at bay.

If there is anything endearing in this collection, it is Prato’s style. She moves easily from revealing story through trustworthy first person narrative to external dialogue, as in this bit from “Minor League Lessons.” Jason is picking up his grandmother to take her out to eat:

It took forever to walk down the hall and out to my car. I tried to be zen about it, tried to just appreciate being in the moment with my Bimbi, noticing the clouds and sky starting to turn orange and pink. More than anything, I didn’t want to be annoyed. She couldn’t help it, and since she’d been forgiving a lot of bad behavior that I probably could have helped, it seemed the least I could do was show some patience. But Jesus, she was slow.

“I want enchiladas,” Bimbi said when we finally got settled in my car. “Good ones, from that place you’re always talking about.”

“They’re kind of spicy,” I said.

“The spicier the better.”

Throughout, Prato employs unique metaphors that place the prose on the verge of poetic, like this passage from “A Proportional Response”: “We eat pie in Suzanne’s living room, and pass another bottle of wine. We wrap our tongues around pumpkin and nutmeg, seeing how far we can stretch small talk before it snaps loose.” These phrases weren’t a constant, but they were smoothly entered into. Anyone with a sense for rhetoric would take notice of this with an appreciation that lets you settle into the story more deeply. It contributes to what makes each one of the works in this collection memorable, and the collection as a whole something to which readers can create a sense of attachment. It is the kind of writing that keeps readers looking for more by an author, and why I’ll remember the name Liz Prato and not hesitate to join her again on the page.