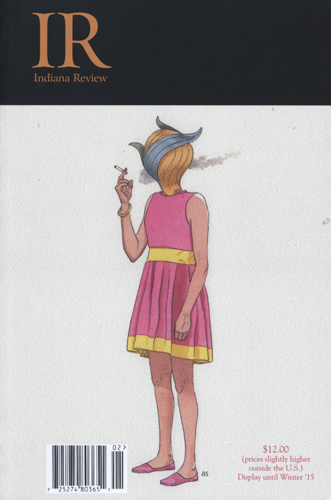

Indiana Review – Summer 2015

Beautifully produced, Indiana Review has fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and in this issue, something called “Special Folio: Graphic Memoir.” With seven contributors, the Special Folio has the look of a comic book. Bianca Stone has two watercolors that resemble greeting cards. Beautifully produced, Indiana Review has fiction, poetry, nonfiction, and in this issue, something called “Special Folio: Graphic Memoir.” With seven contributors, the Special Folio has the look of a comic book. Bianca Stone has two watercolors that resemble greeting cards. “Fragraria” is the story of a strawberry farm, told by the farmer, Arewen Donahue. “The Common Tongue” is diary entries of a Caucasian-Asian schoolgirl in London. In these pieces, the drawings are crude and the stories are banal at times. But “Flying,” has an exciting story by Diane Sorenson and professional graphics by Doug Hansen: a sixteen-year old girl with no training flies a Cessna with her pain-wracked father as copilot.

There are seven short stories this issue. “The Passeur” by E. E. Lyons, the 2014 Fiction Prize Winner, is a scary ride in a taxi from the airport in Kigali, Rwanda to a women’s hospital in Congo. A border guard insists that Madame, the taxi fare, visit his wife, who is dying. The point of view is that of the driver Oudry. What he knows and what he doesn’t know add to the tension.

“A Hundred Ways to Do It Wrong” by Emily Temple tries to be a fable about a father cooking for his daughter’s birthday, but at ten pages it grows tedious. In “Best Behavior” by Vincent Scarpa, a middle-aged woman schoolbus driver in rural New Jersey tells in literary fashion how she teaches memoir writing to prison inmates, marries one of them named Cash, and goes haywire in her schoolbus. At sixteen pages, the joke wears thin.

“Come Go With Me” by Nora Bonner thrives on the traditional values of the short story. A girl tells how her devout Christian father takes her and a troubled male cousin on a summer camping trip. The characters behave in realistic ways, their conflict is sincere, and the last line delivers a jolt: “I realized he was not talking to God, but to me.”

The poetry in this issue varies in style and mood, though all of the pieces can be described as short lyric poems. Gabriella R. Tallmadge has three, Corey Van Landingham has two, and most of the other poets have one. In “After War After War After,” Tallmadge sketches a veteran with deep psychic wounds, but her other poems merely jumble phrases. Landingham’s “King of Hearts” repeats a few images to good effect, to suggest a woman narrator who loves damaged men, starting with her father.

Poems like Marcelo Hernandez Castillo’s “Gesture and Pursuit” shy away from direct statement, to deal instead with foggy, unmoored images. Others like William Fargason’s “On Your Way to Work” use plain language to tell a surreal story. Marianne Chan in “Personalized Wedding Vows for the Twenty-First Century” strikes a sharp note as she begins: “Wear me as a prosthesis.” But the eleven short couplets are arbitrary and ungrammatical, ending with: “only increments of development, / a waitress with no free hands.”

Two nonfiction pieces stretch the idea of nonfiction. “This Is What I Do When I’m Miscarrying” by Amy Collini briefly gives the sad and clinical details. The narrator has a two-year old son to console her. In “An Ocean Existing Somewhere Without Us,” Janelle DolRayne looks at an exhibition of ten “paintings by the abstract expressionist painter Mark Rothko,” one to a page. She sees her own life, including her husband David, while the reader gets scenes that are hard to make sense of.

All of the contributors, it seems, are MFA graduates or about to be, editors of magazines, and teachers of creative writing. If the job of a literary magazine is to promote young writers, Indiana Review does that. If the job is to serve the reader, to present the best new poetry and prose, it achieves partial success.

[www.indianareview.org]