The Iowa Review – Spring 2015

The Iowa Review encompasses texts of the America we assume we know—strong and prideful. Yet, I read about an America whose citizens felt a series of words not synonymous with “strong” or “prideful,” but with “confused” and “defeated.” These American writers (or are they? as some questioned) trudged through turmoil on both native and foreign soil, both within themselves and with the world to compose these words that form a nation of misidentification. The Iowa Review encompasses texts of the America we assume we know—strong and prideful. Yet, I read about an America whose citizens felt a series of words not synonymous with “strong” or “prideful,” but with “confused” and “defeated.” These American writers (or are they? as some questioned) trudged through turmoil on both native and foreign soil, both within themselves and with the world to compose these words that form a nation of misidentification.

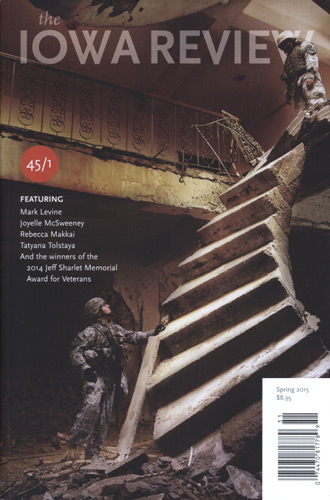

The cover, a photograph taken in Baqubah, Iraq by Stacy L. Pearsall, shows the remnants of a second story building after a series of bombings by American fighter jets. A staircase stands crookedly while a soldier overlooks his comrade from the landing. As the reader turns the page, the inside cover reveals the winners of the Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans. Appropriately the first place winner, Katherine Schifani begins the collection with her essay “Pistol Whip.” Set in the present tense, Schifani brings to light what it is like to be a woman in the military. Despite her sexuality and her girlfriend back home, men still view her as “Captain Beautiful”—an object of desire. She unwillingly uses her body to obtain vital information as requested by Major Jones. Upon her return, she discovers the Major has made up the numbers for which she put herself in danger and asks her, “‘What did you have to do?’” In a sense, nothing but be a woman. But being a woman is everything in the military.

Other stories and accounts of various wars are spread throughout the issue. The most haunting of these, however, are those told by cover artist, Stacy L. Pearsall, and photojournalist, Mary F. Calvert. Pearsall’s “Veteran’s Portrait Project” feature is much like Humans of New York where a beautiful photo is followed by a brief caption that describes the triumphs and hardships of a veteran’s life. Robert “Bobby” Henline stands out, not because of the scars that mark his face from an explosion that killed his comrades, but because of his smile. Known now as “the burnt comedian,” Henline demonstrates how laughter truly is the best medicine. Calvert’s feature is less sensational, touching on what Schifani so boldly brought to attention—rape. The most devastating images are those that are less obvious, such as Brittany Fintel’s photograph with her PTSD dog, Indiana, and TSgt. Jennifer Norris’s testimony to a meager four representatives of the House Armed Services Committee on Capitol Hill.

Not every narrative or poem within The Iowa Review reflects on the trials of serving in the military. Daniel A. Hoyt’s “The Best White Rapper in Brea, Ohio” describes the life of a millennial youth, Kevin, obsessed with Twitter, along with his superstitious mother, catfishing bestie, and a recovering heart surgery patient, who happens to be Kevin’s neighbor, Bruce. Four separate accounts are mingled into one narrative, but they all revolve around Kevin who puts his music out into the void of the Internet, only to be cyberbullied into believing that “[h]e was nothing without technology. Even with technology he was nothing.”

To that end, Michael Fessler’s fiction piece “Listening” comments on the trials of communication in the 21st century. Set in Japan, a burned out American, English professor and part-time haiku poet, Henry, meets a man named Kenzo. Kenzo, like most Japanese, keeps his grief to himself but listens to others and issues them certificates at the end of their conversations. Although we assume that there are people out there listening to us, via our phones, as Henry notes on the train one evening, Fessler uncovers how untrue that belief is. It is through talking to those who are willing to be present in the moment that we learn the most about ourselves, and how to cope with the crippling anxieties that turn us into asymmetrical humans.

In the wake of recent events within the LGBT community, Yuko Sakata’s “On This Side” sheds light on gender dysphoria. Despite the changes in Masato’s (now Saki), appearance, two childhood friends learn how to say goodbye to past versions of themselves and move forward however hurt they were before. Other themes that appear in this issue include dementia—a disorder that has impacted many including myself. Kevin Kopelson’s “Meet Miss Subways” threads together a tragic family history through a series of vignettes. Strangely, his mother’s memories of dancing in school reflect that of my grandmother’s who continuously repeats the steps of her girlhood and insists that I dance as she does.

The Iowa Review is American in every sense of the word, a heartbreaking melting pot of lives and experiences that overlap. Yet, when these tales are united, we are that stereotypical image of strong and courageous.

[www.iowareview.org]