Kestrel – Fall 2013

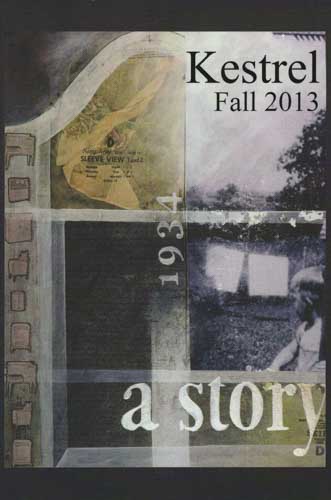

The cover image of Kestrel’s recent issue is a mixed media collage of photo transfer, ink, and colored pencil suggesting a window through which we’re invited to peer deeper into “a story” (the artwork’s title), the text which, along with “1934,” appears as part of the illustration. Artist Julie Anne Struck’s arresting compositions are featured inside the journal as well, collaging image, paint, pencil, text, and texture to results akin to a two-dimensional Joseph Cornell assemblage perfect for the paginated exhibit and super appealing as cover art. As illustrations that beg the viewer to imagine their narratives, what could be more appropriate for this issue’s strong collection of prose and poetry? The cover image of Kestrel’s recent issue is a mixed media collage of photo transfer, ink, and colored pencil suggesting a window through which we’re invited to peer deeper into “a story” (the artwork’s title), the text which, along with “1934,” appears as part of the illustration. Artist Julie Anne Struck’s arresting compositions are featured inside the journal as well, collaging image, paint, pencil, text, and texture to results akin to a two-dimensional Joseph Cornell assemblage perfect for the paginated exhibit and super appealing as cover art. As illustrations that beg the viewer to imagine their narratives, what could be more appropriate for this issue’s strong collection of prose and poetry?

Cathy Barber’s poem “The World” asks us to examine our actions and what we witness in our wakened lives, and Ace Boggess tells us how he’d edit the news to reflect our human-interest angles in “The New Journalism,” both standout poems that speak to our framing of perspective. Boggess writes, “I don’t want to know why the chicken crossed the road / but why he is a chicken when he could’ve been a fish.”

The narratives in this issue explore this question along with how to feel attending an ex-coworker’s child’s funeral after you’ve been fired, what internal click inside the teenage vandal stops his destruction, and much more.

In Jacqueline Doyle’s touching eulogy “Traces of a Life,” the author compiles photographs from her father’s past to represent his unwritten memoir at the funeral service, and in many ways the contents of this issue of Kestrel function in the same way, offering snapshots of the worlds inhabited by the contributing poets and writers and their imagined characters.

In “The Beginning and End of Things,” John Sibley Williams even gives voice to the objects discarded from a life, which we find waxing nostalgic for their purposeful utility and hopeful for an encounter with someone who can use them again. And as Williams looks to the nature of objects in his short story, conversely it is human nature that Robert Johnson and Lee Oleson are concerned with in their smart fictions “A Man’s Reach” and “The Move Out,” respectively.

Our access to human connection outside our own realms of experience is also exceptionally illustrated in Maria Terrone’s “A Facebook Page in Iran,” a poignant perspective on notoriety, social media, and building an online community. Terrone captures an exhilarating, yet discomfiting idea of finding one’s name in an online forum in a language, an alphabet, one cannot decipher.

Carrie Shipers, in her poem “Carry,” explores her own name, personifying the definitions of the verb in a way similar to how Matt Pasca weighs the history ofMatthew in his “In a Name.” In an essay between these two poems, Tim Armentrout presents names of coal companies, their induced diseases, and the desecrated places left behind as a powerful litany/eulogy for the land in “Level Ground.” Matt Zambito, Christopher Beard, Diane Lockward, and Nicci Mechler are additional poets worth noting for their voices, originality, and perspectives.

This issue takes us on an international tour of humanity through short literature and illustration. And the “bang for your buck” factors heavily here; in just 139 pages, this slender volume of Kestrel provides as much as, or more of, the top quality writing you might cull from the annual “Best of” anthologies. Kestrel’s fiction editor, Suzanne Heagy, writes in the issue’s introduction that she hopes the writing and art comprised will “allow readers to imaginatively inhabit worlds they might not otherwise encounter and remember.” The mission is heartily accomplished.

[www.fairmontstate.edu/kestrel]