The Labletter – 2014

The Labletter “has its roots in the Oregon Lab, the name given to a group of artists and their annual gathering.” The magazine began as a way for these artists to stay in contact and share work, and in 2008 it went public—a move fortunate for audiences who care about sophistication, quality, and commitment to art.

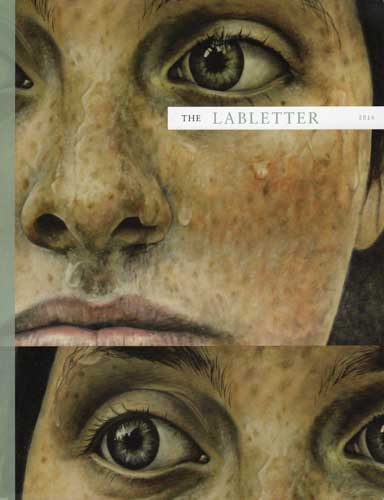

In this issue, you’ll find generously-reproduced art, from the front cover inward; exquisite short stories; three beautifully-crafted essays, on collage, theater, and clogging; and fifteen strong poems by four inspired poets.

The Labletter “has its roots in the Oregon Lab, the name given to a group of artists and their annual gathering.” The magazine began as a way for these artists to stay in contact and share work, and in 2008 it went public—a move fortunate for audiences who care about sophistication, quality, and commitment to art.

In this issue, you’ll find generously-reproduced art, from the front cover inward; exquisite short stories; three beautifully-crafted essays, on collage, theater, and clogging; and fifteen strong poems by four inspired poets. Individually, each is excellent, a gratifying congruence of intelligence, heart, and skill. Together, they are a marvel, earning multiple reads and contemplation. This is a lovely volume.

It’s 8½ x 11 x ¼, pleasing in its design and delicate heft. The front cover is a split image “derived” from Erica Elan Ciganek’s “Befitting,” a close-up oil on plywood of a young woman’s freckled face, unsmiling, tears on her cheeks but no hysteria: a look of knowledge and resignation, rather than of grief or pain. Three more paintings by Ciganek follow inside, all of them close-ups of young people’s faces at moments that seem to follow hard, inevitable news. The detail is compassionate, the effect sobering.

Other artists represented in this issue include Leonora Weissmann, Kouta Sasai, and Brett Eberhardt. Weissmann’s acrylic or acrylic-and-collage pieces depict slightly dreamlike, or fairy tale like, moments, two of hopeful children and two of (different) women in a grotto. Weissmann works in Brazil; her paintings have Portuguese titles. I would like to know their stories.

Sasai’s oil, charcoal, and pencil portraits are haunting images of war and “lost decades” in the Middle East. Eberhardt’s much more mildly-toned oil still lifes feel like miniatures in which fineness of attention makes a small locus—a corner vent near the floor, a blue table against an unadorned wall—feel not only peaceful but cherished.

Attentiveness to the requirements of art, and to the relationship between artist, medium, and subject, pervades the issue. This is as true of the writing as of the visual art. “I’m remembering some collages that my late mother-in-law made after a trip to Cuba in September 1941,” C. R. Resetarits begins her essay “Collage Work: Hemingway, Marion, Martha, Me.” This sentence raises immediate expectations, fulfilled as the piece unfolds: this is about the author’s relationship with her mother-in-law, about collage as art, and about a moment in history, part of whose truth is revealed by art sensitively and defiantly created precisely in that moment. The small accompanying collages, illustrative of the hopes and dreams Resetarits describes in her essay, tastefully supplement the clean, sublimely-paced prose.

“Crazy Legs,” the essay about clogging by North Carolina writer and teacher Susan White, has a different tone but equal stylishness and flair. It begins: “I’ve faked a lot of things in my life—knowledge, orgasms, heterosexuality, fidelity, interest—and the pretense has felt like swallowing dry leaves. But there is one thing I have derived nothing but joy from faking: clogging.” Again, expectations are raised—ah, here’s a voice that doesn’t take clogging any more seriously than necessary, yet loves that lack of seriousness—this should be fun, and interesting, because who clogs? Who fakes clogging and loves it? The story evokes smiles from beginning to end, and, as in every good personal essay, we know, at the end, more about both the subject and the speaker, and are glad of it.

Kate Lu’s brilliant short story “Circuits” typifies the best of the science fiction genre: there’s social critique here (she might be responding directly to Donna Haraway’s 1991 “Cyborg Manifesto,” whose issues resonate even more now), and “characters” we care very much about (are they human or not?)—but the plot surprises knock us off our feet even as they tap us on the forehead: think about this, will you? How can you not?

The Labletter’s policy is to include several poems by each of several poets. Utah poet Holly Simonsen’s six portraits of landscape and atmosphere deftly evoke the paradox of human bodily desires in a desert wasteland. Donna Vorreyer’s four lovely poems are, says her bio, “inspired by the letters of Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell,” but we don’t need to know that to feel their literary heartfulness.

This is, in toto, an accomplished, admirable lit mag. The Labletter editors, and their public, deserve our fervent gratitude.

[www.labletter.com]