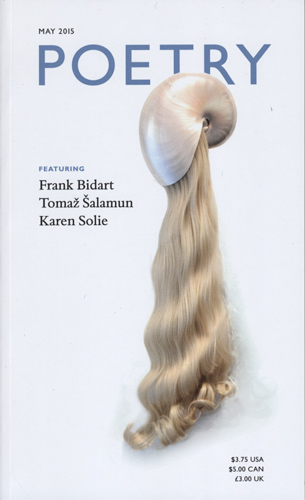

Poetry – May 2015

The May 2015 issue of Poetry prompts us to ask questions, and to observe without judgement the ways in which we act and operate as humans. In the opening poem, Frank Bidart’s “The Fourth Hour of the Night,” a young boy murders his half-brother for stealing a freshly-killed lark, and after, justifies his actions: “He looked / around him. Human beings // live by killing other living beings.” The poem positions us in a setting filled with slavery and brutality, a ruthless desire for power, and the search for immortality. Here, the boy acts based upon what he observes in a world that caters to those “stronger, taller, more / ruthless than you.” The May 2015 issue of Poetry prompts us to ask questions, and to observe without judgement the ways in which we act and operate as humans. In the opening poem, Frank Bidart’s “The Fourth Hour of the Night,” a young boy murders his half-brother for stealing a freshly-killed lark, and after, justifies his actions: “He looked / around him. Human beings // live by killing other living beings.” The poem positions us in a setting filled with slavery and brutality, a ruthless desire for power, and the search for immortality. Here, the boy acts based upon what he observes in a world that caters to those “stronger, taller, more / ruthless than you.” The poem reflects on a history of violence:

Hour in which the earth, looking into

a mirror, names what it sees

by the history of weapons.Hour from which I cannot wake.

“The Fourth Hour of the Night” gives readers a thought-provoking narrative to begin the May issue, an issue that prompts us to consider how we are affected by what we witness, and more so, to reflect on our own behaviors.

We are invited to observe our interactions with the natural world in Karen Solie’s “Bitumen,” a spectacular poem that brings to light our strange habits of traversing and photographing the world while simultaneously destroying it. “[ . . . ] we take selfies. Post them. And can’t undo it,” much like how we can’t undo the destruction we’ve inflicted on the natural world. In Solie’s poem, we don’t get away with it, and the speaker warns that we should get our photos while we can:

before the abundance when,

aflame

in light that dissolves what it illuminates, water climbs

its own red walls, vermilion in the furnaces.

We may distract ourselves with wifi and YouTube, but Solie reminds us that there are consequences for our actions.

Later in this issue, we are introduced to some of the work of the late Slovenian poet Tomaž Šalamun. Of his extensive portfolio of over forty poetry collections, we are offered a sampling of six poems. Translator Brian Henry introduces these works bringing an important reflection forward: “Despite his erudition and worldliness, most of his poems contain questions (there are more than ninety questions in the sixty-six poems in Woods and Chalices), as if implying that the poet’s role is that of the child attempting to grasp the unfamiliar, not of the didactic elder delivering wisdom.” Šalamun’s poems here are frantic, curious, and beautiful. “Alone” comes forward as a creation story, but not in a way we’ve heard it before:

Alone,

I’m alone on the roof of the world and drawing

so stars are created.

I’m spurting through the nose so the Milky Way is created

and I’m eating

so shit is created, and falling on you

and it is music.

As readers, Šalamun’s poems allow us to give in to wild imagination, to accept the unexpected, “To walk empty roads and drink shadows.”

Cathy Park Hong’s essay “Against Witness” begins the Comments section of this issue by examining the artwork of Doris Salcedo. This commentary studies artwork and poetry that bears witness, defining such as that which “is testimony to an exceptionally dark period, embalming a moment where there has been visible, collective trauma.” Salcedo’s artwork is characterized in this way, much like the poetry of Paul Celan, by whom she is inspired. Salcedo is known for her haunting installations made of lived-in furniture, concrete, and clothing that were created in response to horrific events like a 1988 massacre of banana plantation workers. Hong points out that “To make art representing another victim’s pain can be ethically thorny” and that “Images of suffering can arouse our horror, simulating an illusive identification between us and the victim [ . . . ] before we are conveniently deposited back into our lives so that someone else’s trauma becomes our personalized catharsis.” But Salcedo’s artwork responds to suffering differently. She does not expose the “body in pain.” Instead, “There is a somber restrain to her artwork, a silence.” As a viewer, Hong observes that the effect is lasting, admitting, “I cannot escape your disquieting sadness, the burden of your solitude.”

It is through these selections, and the work of other contributors (Sylvia Legris and Daisy Fried to name a couple) that the May 2015 issue of Poetry prompts readers to reflect on our place and function in the world. We are invited to learn from our past, to acknowledge our harmfulness to nature, and to get lost in the imagery of an intoxicating poem, if we choose to.

[www.poetryfoundation.org]