Post Road – 2017

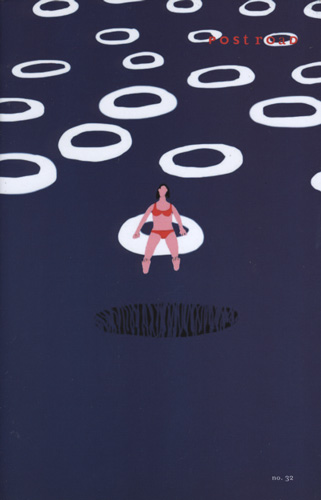

Post Road Number 32 is a complex mix of storytelling that bobs and weaves, delights, and, in some moments, disappoints. The cover piece, a bland, semi-abstract digital drawing by Henry Samelson, is one such low moment, contrasted, incredibly, by the remarkable work of Charles McGill, which sits just inside the issue, seventeen pages away. McGill, who repurposes vintage golf bags to critique class inequality and racial injustice, exhibits a powerful aesthetic that would have made for a much stronger point of entry.

Post Road Number 32 is a complex mix of storytelling that bobs and weaves, delights, and, in some moments, disappoints. The cover piece, a bland, semi-abstract digital drawing by Henry Samelson, is one such low moment, contrasted, incredibly, by the remarkable work of Charles McGill, which sits just inside the issue, seventeen pages away. McGill, who repurposes vintage golf bags to critique class inequality and racial injustice, exhibits a powerful aesthetic that would have made for a much stronger point of entry.

One of the best and most complicated contributions to the issue is “James Dean Posters on the Wall” by Michael J. Hess, an essay that explores death, trauma, and identity. Hess’s discovery of a controversial suicide tome sparks a conversation with his boyfriend about Jim, his boyfriend’s ex, who had used a modified technique from the same book to end his life.

Jim killed himself one November night in Lake View Cemetery in Seattle, Washington. He had taken a mixture of pills and alcohol, fastened a plastic bag over his head with rubber bands, and tied a noose around his neck in such a way that he had to stand on his toes to avoid strangulation. That his death coincided with the birth of Bruce Lee, Lake View’s most prominent resident, does not escape the author, who writes that “he might be remembered by association, by a terrifying self-deliverance that coincided with someone else’s deliverance.”

All told, the essay is haunting and lovely, pulling disparate elements together, weaving a unified whole. Despite the compelling nature of Jim’s story, it makes, at some points, for uncomfortable reading. When Hess describes Jim’s chronic pain and the sexual trauma he’d experienced, he is doing so secondhand, through the stories of a shared boyfriend, Andrew, a neurologist so ethical he apparently won’t give his own family medical advice. Yet here is Jim’s story, out in the world, in all its sad, and moving, and private detail. Does Hess have any right to tell it?

Post Road sets itself apart from other journals by offering criticism and book recommendations. Though they sometimes feel like unwelcome buffers between the stories and the poems, the best recommendations take the form of crafted, informative essays. Dylan Hicks’s piece on the roman à clef Nightmare Abbey by Thomas Love Peacock is witty and informative, tackling technique as well as the characters and their real-life counterparts. In “A Visit to the Antipodes,” a recommendation of the writer Janet Frame, Sarah Lawrence College professor Carolyn Ferrell discusses her attempt to teach the work to her writing students: “Real life, I have always told my fiction students, can be our enemy.” Frame offers her own warning: “Memory is not history [ . . . ] it is a series of retained moments released at random.”

“Suicide and Marrowfat Peas,” a nonfiction piece by Jason Stoneking, follows the writer and his girlfriend, Leslie, as they scrounge an existence in Paris, working on creative projects and seeking out one of the few small, illegal apartments they can afford. Their break comes through an Irishman who knows an American who’d been subletting from a German who’s recently abandoned his apartment under troubling circumstances, leaving, as explanation, a note that reads, “In Paris we live like dogs, when we should be living like kings.” Stoneking’s piece is a tribute to camaraderie, a dare to live boldly, and a reminder that something as simple as luck can divide the sheltered and the homeless, the living and the dead.

The issue boasts a number of lovely poems as well. In “Sacramento,” Elizabeth Gold writes, “He took the bus back to San Francisco. / Daredevil hills. Hummingbirds. Radiant blur that beat / by your ear urgent messages: Here. Yes. Must. Now.” In Ricardo Pau-Llosa’s contribution, a “tipsy Cleopatra [ . . . ] points in spills.” In Major Jackson’s “How to Avoid a Crash,” his narrator “dispens[es] a slaughterhouse of whispers” in the midst of a motel tryst.

Rebecca McGill’s hilarious and occasionally sad piece, “Tell the Children,” centers on a new teacher who thrills her elementary schoolchildren with an avalanche of falsehoods, gifting herself a handsome husband who cooks, travels to Russia, and used to be a fighter pilot. Naturally, it is the children who shine in this story. “Anna with the knack for identifying the interesting, [ . . . ] as her career goal, had chosen I will sing songs to firemen.”

Number 32 is a large, complex issue filled with impressive writing and artwork. There is much more to explore. For those who enjoy but would also like to travel beyond lit journal conventions, Post Road Number 32 is your point of departure.

[www.postroadmag.com]