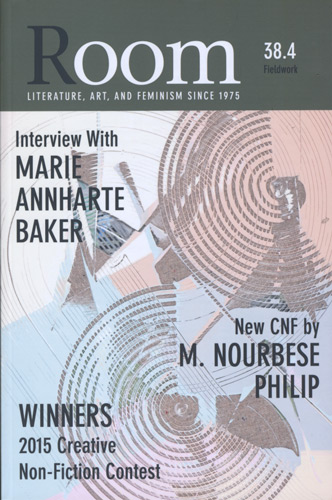

Room – 2015

Room is a Canadian feminist publication of female authors and artists. Issue 38.4, Fieldwork, includes creative nonfiction, fiction, poetry, art, an interview and book reviews. The pieces build upon each other, each work conversing with the ones before and after. The grounding framework of this issue is editor Taryn Hubbard’s interview with Marie Annharte Baker. Baker, a First Nation Anishnabe poet and oral storyteller, articulates that “Storytelling is a way to interact.” And while she refers to oral storytelling, her words ring true to Room where the stories interact with each other. This issue is full of conversations between stories as well as an exploration of silence as interaction. Room is a Canadian feminist publication of female authors and artists. Issue 38.4, Fieldwork, includes creative nonfiction, fiction, poetry, art, an interview and book reviews. The pieces build upon each other, each work conversing with the ones before and after. The grounding framework of this issue is editor Taryn Hubbard’s interview with Marie Annharte Baker. Baker, a First Nation Anishnabe poet and oral storyteller, articulates that “Storytelling is a way to interact.” And while she refers to oral storytelling, her words ring true to Room where the stories interact with each other. This issue is full of conversations between stories as well as an exploration of silence as interaction.

M. NourbeSe Philip’s commissioned nonfiction “Drowning Not Waving” sets the recurring themes of suicide and silence. Philips recounts walking by a man as he jumps from a bridge. Her inaction to comprehend or call the police meets his action to take his own life. Her silence meets the sound of his body hitting the concrete. Her diction reflects these contrasts. Mimicking the man’s fall, Philip’s sentences are designed to trip over: “He did not so much jump as fall. Over.” The language fluctuates between choppy sentences and stream of consciousness to reflect Philip’s confusion. The issue opens with confusion and the subsequent works offer commentary on suicide, silence, or both.

The poem that immediately follows “Drowning Not Waving” offers a different insight into what it means to jump. “Cliff Jumping” by Alessandra Naccarato, depicts a couple living on the edge. The big jump hasn’t come yet. It is still “Two miles to the cliff, where we’d hurl / ourselves like pieces of stone.” Naccarato conveys an action that can still be stopped. Yet, at the end, when the narrator says no, it’s unclear what she’s refusing: her partner’s sexual advances or the oncoming cliff. Naccarato’s poem reflects that sometimes, even when we speak up, we are not heard or understood.

“Horizon-ed,” creative nonfiction by Chelsey Clammer, again visits suicide and continues to build on the foundation Philip and Naccarato established. Examining life after her daughter Sofie’s suicide, Clammer exhausts herself inventing words such as an “un-hearsing” of her grief, or being “Non-Husband-ed.” She says what she can until she can’t: “Here is an essay made from the metaphor of a car and life as a road and how we go until we run out of _____.” The horrifying playfulness of language in a situation where there is no room to play creates an essay honoring where there are no words, not even the ones we invent. “Horizon-ed” serves as a book end, examining the silence Philip initially calls into question.

The most memorable piece is the fiction “Descent” by Dorothea Wojtowicz. “Descent” follows an eight-year old narrator and her friend Aggie. One of the most accessible pieces, Wojtowicz capitalizes on the youth of her narrator to speak plainly to the reader, all the while commenting on class, sexuality and the questions we don’t have the words for. Aggie and the narrator spend their time playing house until Aggie decides on a new game: making a baby. But the narrator’s neighbor sees and later attacks the narrator outside her home. Wojtowicz does not shy away from strong language. The neighbor calls the narrator a “goddamned dyke” and a queer. The brutality of the situation is further highlighted by the narrator’s youth and ignorance. After the attack, she does not have the language to ask her grandmother “was I sexually assaulted?” and instead asks, “Am I a dyke?” Wojtowicz shapes her story around the silence of what’s unsaid yet what the reader will understand.

Room is at its best when the texts reach out to the reader and not just to each other. The poetry, unfortunately, often feels as if it is written for a hyper-educated few. Lakshmi Gill’s poem “Mental Lacuna” replaces words with caret symbols. And while Gill revels in the theme of silence, the poem is a challenge to read. I was not certain I was meant to understand. Room is compelling when the work does more than play with silence and recurring themes but reaches out a hand to converse with the reader.

Issue 38.4 of Room probes life’s silences, and the way one piece can inform and comment on another. Returning to Marie Annharte Baker, she describes the threads connecting women writers as “a mother line” making it all the more relevant that the text is an exploration of women’s conversations and silences. Room upholds its feminist roots, giving female authors a place to speak to each other.

[www.roommagazine.com]