Salamander – Summer 2012

Volume 17 Number 2

Summer 2012

Biannual

Justin Brouckaert

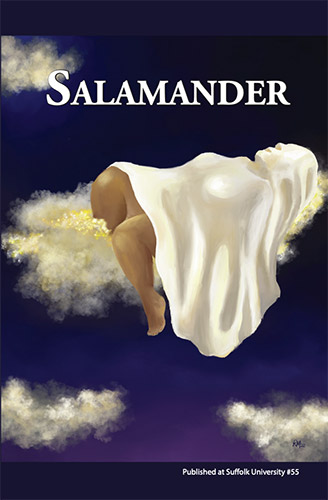

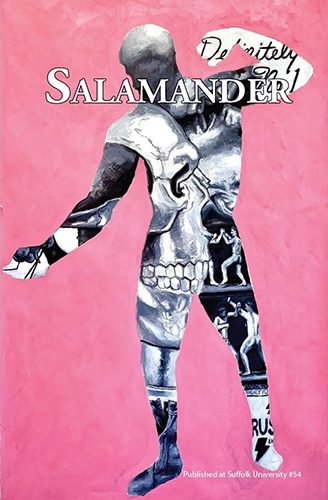

They say not to judge a book by its cover, but to be honest, I do it all the time. Of course the work in a journal always ends up speaking for itself, but I’d be lying if I said first impressions didn’t influence the way I approach new lit mags. In this case, between the title and the cover art, Salamander had me feeling a bit uneasy.

They say not to judge a book by its cover, but to be honest, I do it all the time. Of course the work in a journal always ends up speaking for itself, but I’d be lying if I said first impressions didn’t influence the way I approach new lit mags. In this case, between the title and the cover art, Salamander had me feeling a bit uneasy.

As it turns out, my gut was right: I wasn’t ready for Salamander. Fortunately, this issue was surprising and even discomfiting in the best of ways: daring, absurd, awkward and playful.

Salamander’s all-fiction issue includes stories that reflect, according to Senior Editor Peter Brown, “two of the primary debates raging in America at the moment: war and health care.” This link, however, is incidental; Brown says that the selection process for him and Fiction Editor Catherine Parnell was much simpler: “We both knew it when we saw it.”

There is indeed something distinct about each of these stories?often just a subtle moment or a well-placed line that stands out and defines the work. It starts with the title of the first story (Katiea Kapovich’s pleasantly absurd “Who Will Save Batman”) and doesn’t end until the final line of the final story (David Abrams’s “The Bridge”), a phrase that emphasizes the mundane repetition of military routine and everyday life for American soldiers overseas: “And it’s never gonna stop.”

Siobhan Fallon’s “Tips for a Smooth Transition” also hones in on an aspect of military life: in this case, a woman named Evie welcoming her husband Colin home after his deployment in Afghanistan. The story is separated by quotations from Battle Spouses’ Tips for a Smooth Transition, a book that Evie is reading. The advice the book offers is constantly clashing with reality, and that’s not the only obstacle for Evie and Colin. The two have different ideas about what life should consist of after Colin’s return: he wants to kayak, surf and swim with sharks, while Evie would rather spend quality time talking to her husband and pursuing more leisurely activities.

Despite Colin’s new penchant for danger and a brief moment of infidelity that Evie can’t bring herself to confess, she eventually finds a sort of comfort in him being home, embracing the security she feels in the two of them being together, at least for the time being. It is this acceptance that defines the story.

“You’re OK. I’m here,” she says over and over like a lullaby. She’s not quite sure when the refrain changes to “I’m OK. You’re here.” She does not think of all the years ahead, when she will be alone again. Colin is here, and Evie is content. At last she is certain of what she needs: her arm around her husband’s chest, his warm breath on her wrist.

In Sarah Hulse’s “Breakwater,” the moment that grabbed me and made me cringe until my jaw hurt was when Elias embraces his niece as if he is her father, his identical twin and a war photographer who disappeared in Yemen and is assumed dead:

She looks at me another long moment, then comes around the table and climbs onto the couch beside me. “I missed you a lot,” she says. I can feel the words on my chest, her breath warming the fabric of my shirt.

I stroke my hand over her hair. Her head is warm beneath my palm, her hair damp where it clings to her neck. Oh, this child, this piece of him. “I missed you too, Beanie.”

Hulse doesn’t show this moment just to make her readers squirm in their seats, however. Throughout the story, Elias struggles to admit that his brother may be dead, feeling that if something had truly happened to his identical twin, he would feel it. This attempt at impersonation, at preserving his brother in his own actions, hints that the truth about his brother’s death is finally winning over, much like the weather that overpowers Elias in the final scene when he observes that “everything is sharper and harder and stronger, and me feeling it less and less and less.”

Other gems include Shane Castle’s “Loch Ness Bigfoot,” a story about bigfoot moving to Loch Ness in search for peace, quiet and his kindred spirit, and E.A. Neeves’s “The Bowrider,” a story that is daunting in its hopelessness, leaving its readers feeling as trapped as the teenagers that were looking for adventure and ended up beached on an abandoned island without food, water, a boat, or a prayer.

This issue is worth reading. It’s worth cringing at and laughing at and questioning. Here is my advice: Don’t judge; just let the work leave you out for the sharks, drowning in the sweat of awkward confrontations, finding comfort in the hope that while Salamander may leave you stranded on a deserted island, it will certainly bring you back with stories to tell.

[www.salamandermag.org]