The Austin Review – December 2014

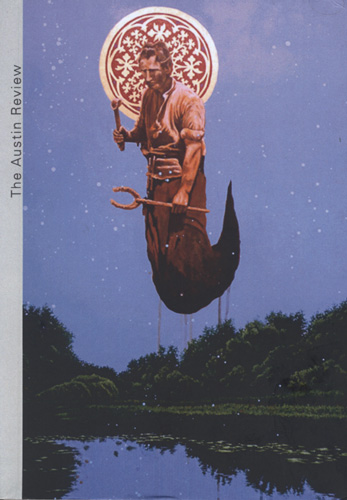

What initially drew me to The Austin Review was the delivery. A sucker for small-sized publications, the compact journal called out to me as soon as I saw it. Even putting biases aside, the beautiful cover art, “Iron Age” by John Mulvany, which features a serene night scene with a ghost lighting up the sky, would’ve been enough to draw me in.

What initially drew me to The Austin Review was the delivery. A sucker for small-sized publications, the compact journal called out to me as soon as I saw it. Even putting biases aside, the beautiful cover art, “Iron Age” by John Mulvany, which features a serene night scene with a ghost lighting up the sky, would’ve been enough to draw me in. In an interview with Mulvany on The Austin Review website, he says:

I have been painting ghosts for several years—mainly as a visual metaphor for memory. . . . My work reflects on the past in the context of our supposedly advanced society, which oftentimes seems to be regressing, particularly with the recent upswing in hostility towards science, education, rationality, and humanism.

Mulvany’s ghosts echo into some of the writing this issue, especially seen in “Alex Gehry Changed His Status to Single” by Jason Hill and “An Execution” by Gabe Durham.

Durham’s nonfiction piece follows the 2011 execution of Derrick O’Neal Mason for the shooting of Angela Cagle, seen through the eye of an online news article’s comment section. The piece resounds with authenticity with usernames like “1978gump” and “USMCDad” saying things like, “he won’t be able to do that because he is headed SOUTH (hell) not NORTH (Heaven) where Angela is.” The hatred and desire to see a man killed coming from faces hidden behind screennames is chillingly real. Anyone who’s even just skimmed the comment section of an article will connect with the creative way this piece of the past is presented.

Hill, in “Alex Gehry Changed His Status to Single,” creates a work of fiction that feels real enough to have happened in my own group of friends. After Alex and his girlfriend Heather make their break-up “Facebook official,” their group of friends dissect and analyze the likes and comments that accompany the virtual change. Family members, friends from the past and present, and potential future love interests all pass under the microscope until it’s turned inward:

The whole thing about social networks in general, we argued, online or otherwise, is how it is all divided parts of you, how those parts see what they want to see and combine to define us, rightly or wrongly. Who the fuck can stop people, whether they are on Facebook or not, from seeing what they want? People, we emphasized, not us, and then said to each other, Right, of course not us. At least not to the same extent, we qualified, and said again, Right, of course.

Hill leaves us examining our own selves and relationships on and offline, a perfect piece for this period of time.

There are three other nonfiction (Truth) works and three fiction (Lies) works, the latter including “Firebuddies” by KT Browne in which Toddy, the narrator, collects fireflies to let them gently die in jars to save them from this world. Toddy imagines a mouse trapped in the wall, needing help, as their mental health deteriorates. Dripping with desperation and beauty, this is one of the stories that makes the fiction a bit stronger than the nonfiction this issue.

“Metronome” by Stephen Parrish is as haunting as Mulvany’s cover art. The narrator’s brother Samuel rocks his bed into another world where he’s closer to his sibling, remaking their old memories so they have better endings. Parrish creates magic in this time-travel piece, the ending leaving me wanting more—the next chapter to the siblings’ story.

The last work of fiction, “Salt” by Christine Fischer Guy, follows a couple as they drive, the woman worrying over their relationship. Also included in this issue is a feature with three flash fictions by James Tate, whose writing falls across the page in rapid fire.

“Beautiful Stuff” by Zoe Bossiere became my favorite nonfiction piece, comprised of two paragraphs. The first paragraph is a list of ‘treasures’ children are carrying with them: “colored yarns, birthday ribbons, river rocks [ . . . ] hair ties, lost buttons, striped paper clips, novelty pencils . . .” and the list goes on. In a short space, Bossiere manages to make me see the beauty in their bright innocence and their treasures and remember when I had my own treasure trove of trash as a child.

With time travelers, phantom mice, and long night drives, the stories in the Spring 2015 issue are perfect for the lengthening days and reading beside the fire. Whether haunted by the ghosts of memory, or by the ghosts of Browne’s dead fireflies, this issue of The Austin Review will follow readers around long after they’ve put it down.

[www.theaustinreview.org]