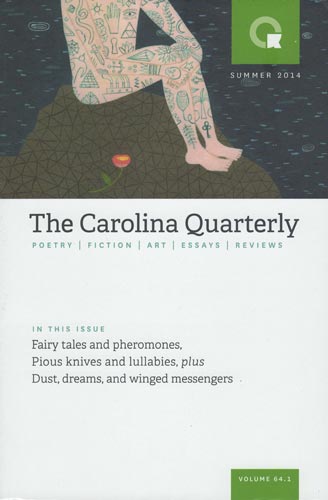

The Carolina Quarterly – Summer 2014

According to the cover, the Summer 2014 edition of The Carolina Quarterly is said to be full of “fairy tales, and pheromones, pious knives and lullabies, plus dust, dreams and winged messengers,” but it’s also chock full of darkness and hope, especially in the fiction and nonfiction entries. The Summer 2014 edition takes readers on a roller-coaster ride of loss, love, and optimism.

According to the cover, the Summer 2014 edition of The Carolina Quarterly is said to be full of “fairy tales, and pheromones, pious knives and lullabies, plus dust, dreams and winged messengers,” but it’s also chock full of darkness and hope, especially in the fiction and nonfiction entries. The Summer 2014 edition takes readers on a roller-coaster ride of loss, love, and optimism.

Dan Moreau starts the ride with an interesting religious, caste-system tale of modern day living in his fiction story “The Line.” Villagers of all backgrounds stand in line in order to meet with the king, who they hope will better their lives. But as in life, Moreau points out that many of the ones that need help the most will never reach the king and others will be turned away for no reason, while the rich and powerful find an alternate route to see the king through an entrance of exclusion. But the underlying reason they continue with their plight is hope. Everyone clings to the idea that something good will eventually come their way. Moreau’s story also takes on religious undertones as some villagers openly question if there is a king while others set up their own village with their own rules and regulations. Though some split off into different sects, many, like sheep, never give up because “They can see it now. They are almost there. They are all so close.”

Aaron Sanders continues the religious ride in his fiction story “Upon the Ground,” a story of a homosexual clergyman that can only cleanse himself by being executed by members of his church. Sanders amped up the religious undertones with his characters’ names as well, having Jonah married to Mary with a son named Peter. Sanders’s story tackles the long-standing debate among many organized religions about homosexuality in a fresh way, showing how zealots feel the need to destroy things that they are unfamiliar with, despite the harm it will cause to others. In the end, Sanders cleverly shows that Jonah, like Jesus, is willing to give his life for the betterment of his family.

In the nonfiction piece by Nathan Scott McNamara, “Parole,” personal identity again creeps in the fray as McNamara tries to come to grips with his friend’s recent felony charge for marijuana possession. Like Jonah, McNamara’s friend, Travis, is saddled by a label that will cause issues throughout his life. While the ending is a bit ambiguous, McNamara makes some valid points about how outdated drug laws allow something as innocent as marijuana possession to destroy someone for life.

Jason Shults’s nonfiction piece “Finer Than Prayer” doesn’t carry the same religious undertones as some of the aforementioned stories, but Shults does delve deep into personal identity, sexuality, and control in his memoir. Shults’s piece is cleverly driven by smell—pheromones to be exact—in an attempt to grapple with the nurture vs. nature dispute that runs rampant in debates about sexual identity.

Lynne Stoecklein’s “Ashes, Ashes” is a gem of a love story. The short story chronicles an aging widow traveling with the ashes of her late husband around Italy, fearful to let him go for good. Stoecklein’s work looks into the hurt caused by losing “the other half” of yourself and how to carry on with your life afterward.

The final two stories, “All Who Answer Are Chosen” by Ken Huggins and “Wildlife” by Anne Korkeakivi, are well-written, coming-of-age stories where the protagonists experience epiphanies after near-death experiences. Huggins’s short story is part fairytale and part reality, starting with three boys playing in the woods and ending in the “Underworld” at the “Pool of Edon.” Huggins straddles these worlds with a deft touch, never straying too far into the other realm to lose the reader. Korkeakivi’s story doesn’t stray into the ethos, but it does continue the theme of hope that is found in many of the stories in this edition. After nearly dying in an accident and being left alone in the hospital, Lydia clings to the belief that “Everyone is where he or she should be.”

While I focused my review specifically on the fiction and nonfiction pieces, the issue does contain poetry by P.J. Williams, Michael Lavers, Matthew Harrison, J. Camp Brown, Autumn McClintock, John Blair, Matt Morton, Farah Marklevits, Kate Partridge, Bob Watts, Jory Mickelson, George Bishop, Alicia Rebecca Myers, Virgil Renfroe, and Joseph Mulholland. In addition, the issue also features two distinctly different collections of art. Noa Snir’s “Scheherazade” is a colorful collection of work, while Phillips Saylor Wisor’s sketches made from recycled materials are a more minimalistic compilation.

[www.thecarolinaquarterly.com]

Reviewer bio: Paul Warner earned his B.A. in Interdisciplinary Studies, focusing on Journalism and Mass Communications, from Coastal Carolina University in 2000. Following graduation, Warner worked as a motorsports reporter for The Sun News for three years before being hired by the USAR Hooters Pro Cup Series as a media relations director in 2003. Warner joined the NGA Pro Golf Tour as media relations director in 2009. Warner’s stories have been published in various newspapers, trade publications and websites across the country. In 2014, Warner entered the Master of Arts in Writing program at CCU to focus on creative nonfiction.