The Gettysburg Review – Autumn 2014

The Autumn 2014 issue of the Gettysburg Review is utterly absorbing. Its writers are not coy about the heart of the matter; readers know exactly what they’re trying to get across. It is very accessible reading. The most straightforward sentence is also fresh, and the most commonplace sentiments come wrapped in stories that linger. In “The Woods Are Never Burning,” Steven Schwartz weaves together different strands of his childhood and adolescence in Chester, Pennsylvania, anchored by his eternally optimistic furniture salesman father. In the background, there is the quiet hum of racial tension, the strangeness of growing up, and changes to Chester itself. Marian Crotty recounts the beginning of a romance in “Love at a Distance,” where the narrator is in Dubai and her lover, Chicago. The language has a touch as light as a ballerina on pointe: “When we talk, it is almost always on the edges of sleep, one of us newly emerged from the unconscious and the other ready to fall.” The Autumn 2014 issue of The Gettysburg Review is utterly absorbing. Its writers are not coy about the heart of the matter; readers know exactly what they’re trying to get across. It is very accessible reading. The most straightforward sentence is also fresh, and the most commonplace sentiments come wrapped in stories that linger.

In “The Woods Are Never Burning,” Steven Schwartz weaves together different strands of his childhood and adolescence in Chester, Pennsylvania, anchored by his eternally optimistic furniture salesman father. In the background, there is the quiet hum of racial tension, the strangeness of growing up, and changes to Chester itself. Marian Crotty recounts the beginning of a romance in “Love at a Distance,” where the narrator is in Dubai and her lover, Chicago. The language has a touch as light as a ballerina on pointe: “When we talk, it is almost always on the edges of sleep, one of us newly emerged from the unconscious and the other ready to fall.” When traveling with the husband in “The Successful Husband” by Edward Porter, the reader is always wondering whether things are going to end well; just as we are almost convinced, and even touched, we are surprised again. In “Zeit und Raum,” Mary Alice Hostetter remembers her year in Helvetia, West Virginia, as a year in which she learns that for many things, “there is no hurrying.” The piece is a beautiful pastoral. “The Parchment Is Burning, but the Letters Soar Freely” by Judith Edelman stands out from the rest with its more elaborate conceit: a cat was made into a handbag by its fashionista owner and observes her life with a dispassionate eye. The language of physics and philosophy peppers the story and gives the cat a distinctly sardonic and very enjoyable voice. Jill Storey ruminates on life in its elemental form in “A Clutch of Eggs.” The meditations are by turns hopeful and elegiac without tipping into sentimentality; in fact, they evidence moments that were deeply felt and deeply lived.

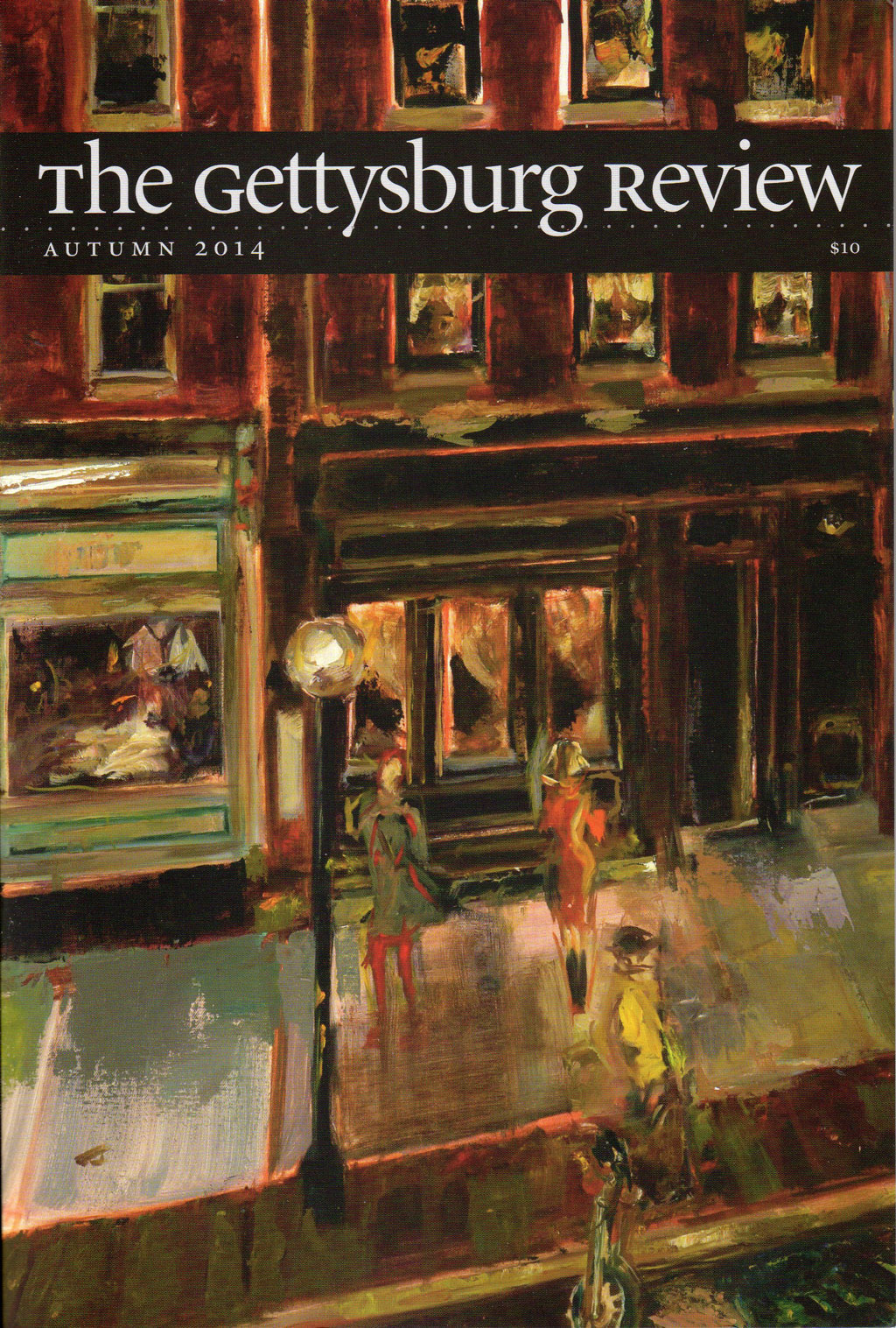

Such depth is also evident in Catherine Arnold’s paintings, printed with an essay by the artist. My favorites are the portraits that bookend the selection: Nell, of an older woman with a “keenness and integrity” (the artist’s own, and perfect words) in her face, and Push Your Face Toward the Early Light, of a younger woman with paintbrushes in her hand and the hand touching her mouth, her face turned toward the light in a thoughtful expression. She seems to have paused in the middle of her work, but one feels as if the moment has been made eternal. In between are landscapes with lush colors and almost-fantastical compositions that mesmerize the eye and the imagination. The cover, a detail from On Liberty, features a street with a few figures that seem to be caught in movement and a building with a brilliant, coppery exterior. In the essay, “The Painting of Nell,” Arnold captures a few snapshots of her artist’s life and her personal encounters with the subjects of her painting, interspersed with her own reflections on growing older.

The poems are never far from everyday experience: two turtles mating (“Morning Run,” Michael Waters); a child’s certainty about a very large abstraction (“Love’s Last Number,” Christopher Howell); “humdrum nothingness” at train stations and art museums (“Words Ending With a Line from Szymborska,” Tony Sanders); a woman caught in a flood in West Virginia coal country (“Coal,” Thomas Reiter). But the poems also never seem to be in the world; they stand a small distance apart, as if separated by a veil and filtering the world in mimicry of an individual’s experience of it. The result is often a sense of solitude, even in the midst of a crowd.

The pages in the Autumn 2014 The Gettysburg Review are as enthralling as the intense fall colors on the cover. They are well worth your while.

[www.gettysburgreview.com]