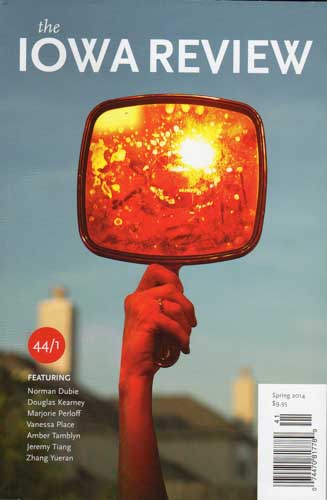

The Iowa Review – Spring 2014

Iowa is often considered a fabled place in the world of American letters, and The Iowa Review lives up to the expectations that such a powerful name bestows. The journal has been publishing some of the country’s finest authors since 1970, and in 2014 it’s still incredibly strong.

This issue, the first with Editor Harilaos Stecopoulos at the helm, includes poetry, fiction, essays, and artwork, all consistent with the journal’s previous issues. The issue also includes two interviews and two reviews, both new features, as well as a pairing of three Amber Tamblyn poems with images by, among others, filmmaker and painter David Lynch.

Iowa is often considered a fabled place in the world of American letters, and The Iowa Review lives up to the expectations that such a powerful name bestows. The journal has been publishing some of the country’s finest authors since 1970, and in 2014 it’s still incredibly strong.

This issue, the first with Editor Harilaos Stecopoulos at the helm, includes poetry, fiction, essays, and artwork, all consistent with the journal’s previous issues. The issue also includes two interviews and two reviews, both new features, as well as a pairing of three Amber Tamblyn poems with images by, among others, filmmaker and painter David Lynch. In the editor’s note, Stecopoulos indicates that while he expects the journal to continue much of what has made it so successful over the years, such as its eclectic mix of styles and aesthetics, he also hopes to see it push forward. Other collaborations of visual art and literature are forthcoming, and readers can look forward to Shaun Tan’s illustrations of Grimm’s fairy tales in a future portfolio on children’s literature.

The journal does indeed feature, as Stecopoulos claims, an eclectic mix of writing. In poetry, there is a world of difference between the styles of Melissa Broder’s brilliantly casual “Hope This Helps” and the tightly knit verse of Sarah Crossland’s “The Boy Who Drew Cats.” The prose also ranges widely in topics and style. There is an essay about Liberace (Kisha Lewellyn Schlegel’s “Liberace and the Ash Tree”) and an essay about hoarding (Robert S. Brunk’s “Selling Everything”). There is fiction that features two different types of off-kilter realities: one based in historical fact, following the aftermath of Cherynobyl (Maria Kuznetsova’s “The Accident”), and one that is speculative, a narrator driven to his limits by the appearance of mysterious poles popping up through the neighborhood (Joe Aguilar’s “The Poles”).

Mai Nardone’s “Beneath the Mountain” follows a narrator at the cusp of womanhood as she spends a “summer at the shore” in New Jersey. There are no huge dramatic peaks in the story, but it is still a story well told—Nardone has a keen eye for what keeps a reader interested in a narrative, and “Beneath the Mountain” has it all. The narrator navigates issues of young womanhood, including a changing body, a dissatisfied mother, and an unrequited crush on a boy who falls instead for a more “mature” classmate the narrator meets and befriends on the beach. Nardone chronicles a season of change, an emotionally gripping one at that.

Although “Beneath the Mountain” is a fairly straightforward narrative, Robert S. Brunk’s “Selling Everything” is considerably more reflective. The essay investigates possession, asking questions about wealth and excess, what a person needs to be happy. The narrator tells about his time working in the auction business, about discovering the valuables that lay hidden in people’s estates (often in squalid conditions), and what people were or weren’t willing to part with. Bookended by an anecdote about the time he found valuable pianos at the former estate of televangelists Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, Brunk uses his experiences in the business to talk about his own connection to valuable possessions, asking, “[f]rom where does the need to accumulate things arise?”

I’ve long been a fan of Melissa Broder’s poetry, and I found “Hope This Helps” to be, if not one the best of the poems in this issue, then at least the one most closely linked to my own aesthetic preferences. As always, her work immediately announces that it’s not afraid of being strange:

My friend channeled the universe

when he said I was milk.

My friend said I was born milk

but then grown-ups poured in lemon juice

which makes sense

because I’ve always felt like rotten cottage cheese

Amid the talk of milk, the different lenses in which Broder explores the concept of milk, the poem punches you with moments of startling perception that leave you staring off into the clouds, like when the narrator in this poem admits, “I don’t think this is a story about blaming grown-ups / for the ways we are ruined.”

If The Iowa Review isn’t on your radar by now, you have no excuses. It’s simply an impressive publication. And though the name Iowa may bring to mind traditional mainstays like Flannery O’Connor or Raymond Carver, the journal produces a sampling that accurately reflects the diverse and constantly changing state of the contemporary literary world.

[iowareview.org]