Tin House – Fall 2017

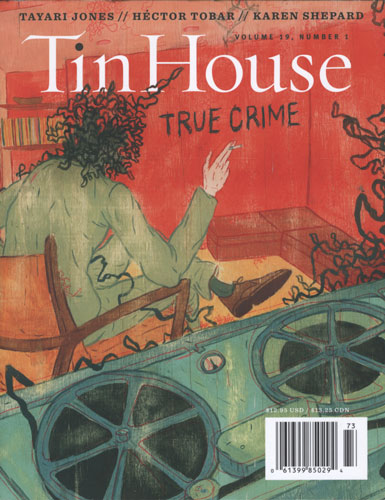

Volume 19 Number 1 is the “True Crime” issue of Tin House, designed, according to Editor Rob Spillman, “as a way to engage our country’s voyeuristic obsession with rogues and outlaws.” While vintage scraps of American morbidity do feature in this issue—the Starkweather murders, the Kansas village made famous by Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—social justice and the criminal state share equal billing. In the latter poems and stories, black and brown lives are pulled apart by oppressive forces emboldened by a complicit public. The gateway to the issue, Sean Lewis’s portrait of record producer Phil Spector, is dark and almost whimsical, a perfect point of entry. Lewis replaces Spector’s head with tangled tape, evoking a wig worn at his trial, as well as the “confused mind” that would lead him to murder actress Lana Clarkson in 2003.

Volume 19 Number 1 is the “True Crime” issue of Tin House, designed, according to Editor Rob Spillman, “as a way to engage our country’s voyeuristic obsession with rogues and outlaws.” While vintage scraps of American morbidity do feature in this issue—the Starkweather murders, the Kansas village made famous by Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—social justice and the criminal state share equal billing. In the latter poems and stories, black and brown lives are pulled apart by oppressive forces emboldened by a complicit public. The gateway to the issue, Sean Lewis’s portrait of record producer Phil Spector, is dark and almost whimsical, a perfect point of entry. Lewis replaces Spector’s head with tangled tape, evoking a wig worn at his trial, as well as the “confused mind” that would lead him to murder actress Lana Clarkson in 2003.

The issue opens with an excerpt from Tayari Jones’s forthcoming novel, An American Marriage. It features a couple, Celestial and Roy, whose already rocky marriage is plunged into greater chaos, or perhaps strengthened, by an unfounded accusation. It is a strong, standalone excerpt that closes with a powerful bit of prose. Jones writes, “I don’t know how long we lay there, parallel like burial plots. Husband. Wife. What God has brought together, let no man tear asunder.”

Hafizah Geter’s following contributions are poetic testimonies on behalf of Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, and Sandra Bland, whose deaths—at the hands of police or in police custody—sparked and sustained large-scale protests of police violence and prejudice. It’s clear that Geter means to honor the fallen, but her first three contributions are persona poems, channeling the victims in their final moments, attempting to inhabit the dead, a technique that is both powerful and disrespectful, the artistic weaponization of deaths that are so immediate, of moments, final moments, that are sacred, and private, and unknowable. The “TESTIMONY” for Sandra Bland is different, set in second person, an address rather than a summoning; it is beautiful. “After the miscarriage, you moved to Waller County / wearing the ghost of motherhood / and wanting to make old wounds foreign.”

In “Murder Tourism in Middle America,” Justin St. Germain chronicles his trip to and through Holcomb, Kansas, the site of the Clutter family murders, made famous by Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. St. Germain, who was, at the time, making final edits to a memoir about his own mother’s killing, had grown increasingly frustrated, even enraged by Capote’s work, which he’d read a half-dozen times and came to see as “a cornerstone of murderer worship in American culture.” The essay is fascinating, providing insight into Capote’s many fabrications and explaining how an entire industry was birthed from this seminal work. Also under the microscope is St. Germain’s romantic life, which is marked by seeming disdain for his “de facto girlfriend,” whom he later rushes to, in a self-described panic, with a ring in his pocket. The essay is engaging, enlightening, and pleasantly divergent. Whether or not it is “factually immaculate,” as Capote touted his book to be, it communicates pain, criticism, and self-reflection in a truly seamless way.

There are numerous other contributions of note, including Héctor Tobar’s “Hillsides and Flatlands,” an essay that explores parallel worlds—violent and safe—in mid-nineties Los Angeles. In “Double Exposure,” Liza Ward unpacks the murder of her grandparents, victims chosen at random by Charles Starkweather, and condemns the widespread fetishization of crime scene artifacts that required her to seek out complete strangers in search of family mementos and unreleased crime scene photos. Her essay is a spiritual twin to St. Germain’s. In a series of sonnets, each titled “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin,” Terrance Hayes deftly evokes an aggressive America marked by white picket fences that sit like spears in front of suburban mansions, critiques white America’s subliminal reclamation of the n-word through music, and sings battle songs to Death.

Not every piece in the issue has an obvious tie to the theme of “True Crime,” but this bit of editorial flexibility has led to a fairly astonishing breadth of content. At their core, these are the stories of storytellers, with a few potshots at the current president thrown in. Tin House has a habit of making itself essential reading, and this issue is no exception. For those interested in American literature, in our darkness and in our light, this collection of prose, poetry, and artwork is calling out, a record of our times, a reminder to seek brighter paths where they may be found.

[www.tinhouse.com]