Witness – Spring 2017

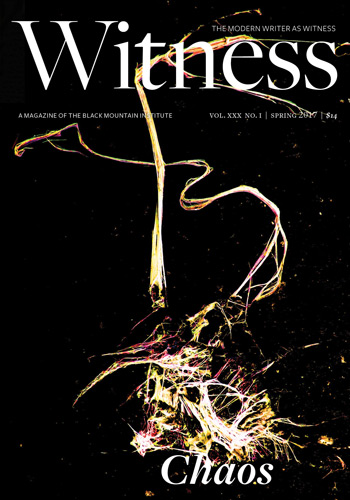

Chaos is the theme of this year’s issue of Witness, and there is plenty of it going on. Start with cover photos by Alexandre Nodopaka, who interprets the chaos of the cosmos. Artists use all sorts of unexpected media, but Nodopaka looks no further than a parking lot surface underfoot to discover “cosmic inspiration in seagull guano.” He states, “The guano, in their ethereal impacts on the macadam, up close, portray the likeliness of astronomical photographs of the heavens.” A series of his “highly light-contrasted” photos, some resembling Rorschach tests, are featured within.

Chaos is the theme of this year’s issue of Witness, and there is plenty of it going on. Start with cover photos by Alexandre Nodopaka, who interprets the chaos of the cosmos. Artists use all sorts of unexpected media, but Nodopaka looks no further than a parking lot surface underfoot to discover “cosmic inspiration in seagull guano.” He states, “The guano, in their ethereal impacts on the macadam, up close, portray the likeliness of astronomical photographs of the heavens.” A series of his “highly light-contrasted” photos, some resembling Rorschach tests, are featured within.

Other concepts of chaos are just as compelling in this predominantly prose issue. Explosions get good mileage in Michael Zadoorian’s “To Make a Noise” and Amanda Futrell’s “Bravo.” Zadoorian leads me to believe his protagonist makes a bomb “to drown out noise,” then surprises me with his reveal.

But Futrell’s story is the one I can’t forget. Here is her knockout first line: “Sergeant Chris Bergdorf had watched his son burst open at least twenty times that morning.” What follows reaches deep into a soldier’s return home from war, as Bergdorf constantly imagines harm coming to his six-year-old son Bravo. It escalates into reality when Bravo has a typical childhood accident that normally wouldn’t produce chaos. Futrell is a skilled writer and should be headed toward wider recognition.

In the nonfiction category, “Gleipnir,” by September Liam Valentine, begins with a toddler, then subtly shifts to a Nordic myth. The mythical gleipnir is actually “the impossibly strong silken ribbon [ . . . ] forged from six supposedly impossible things” that include the sound of a cat’s footfall and the breath of a fish.

We are privy to Valentine’s background: “I had a stroke in utero that left me mildly palsied on my left side, I have jerked between definitions for most of my life.” Though Valentine practices the dharma, “nothing prepared me for the impossibly gentle hand of a toddler named Oliver wrapped around my finger.”

Susan Sterling calls her essay “Dr. Hunt,” and leads us to the nursing home where her dad lives in the Alzheimer’s wing. She perfectly encapsulates the feelings of anyone whose parent has the disease: “[ . . . ] I was searching for a person who had gone missing. I was looking for my father, who he had been, who he was still.”

Another piece among the nonfiction selections is Andrea Patton’s “Flights.” Patton graduates from being a fearful child to becoming a world traveler who still hasn’t put her fears to rest. One announcement on the Russian carrier Aeroflot relays the startling news that “Moscow’s air traffic controllers had turned off the runway lights and left the airport for the night.” But “Not to worry, the pilot assured us: he would dump the remaining fuel and line himself up with the dark runways from memory.” An even more heart-stopping moment comes as she’s heading for Boston when the World Trade Center is attacked in 2001. Nevertheless, “I understand that travel is what propels me—I can’t be content to stay on one path for long.”

Other chaotic situations in this volume deal with flying rodents, as in Sadie Shorr-Parks’s “Attic Bats, Modern Love”; a fatal car accident in Charlene Logan Burnett’s “Thirst”; and a mysterious phone caller in “Mr. Masterson, Your Flight Awaits,” by David Heronry.

For poetry lovers, Witness includes a sprinkling of splendid work. I’d like to have seen even more selections. After all, the theme of chaos is so wide open, it would be interesting to read other poetic expressions on the subject. However, the poems included are quite appealing.

Candice Reffe chooses a tiny insect as a trigger in “My Life Shrinks to the Size of a Midge”:

The one that flew into my mouth, its wet wings banging

my throat cage, the bloated scent of sea, low decibel

feeling something’s coming inexorable as a red

dress,

Sara Henning’s trio of poems begins with “The End of the Unified Field,” which contains these luminous lines about spreading her grandfather’s ashes:

I watch his body glitter the air

like diamonds. I watch him rise through sun-stained fields

of soybeans, deform the ether with his vector field,

each fleck of him a stippled star.

Likewise, G.C. Waldrep has a winning way with words in “Epitaphion”:

Dead-nettle empurpling the freshening fields—

some god is combing this oily wool, has sent his little

kleptomaniacs into the glistering world. Some god’s

hand lies heavy on the molded features of your still face.

The 2017 issue of Witness is vibrant with new and established talent. It is an excellent choice to transport any literary fan into the company of inspired writers.

[witness.blackmountaininstitute.org]