Wordrunner eChapbooks – Summer 2018

I generally don’t like to play favorites, but chapbooks are hands down my favorite books to read. Fiction, nonfiction, poetry—it doesn’t matter. If it’s a chapbook, I want to get my hands on it. Wordrunner eChapbooks offers a twist on the usual chapbook by bringing them online. Dedicating each of their issues to one writer, they create a digital chapbook, a great little showcase of one author’s work.

I generally don’t like to play favorites, but chapbooks are hands down my favorite books to read. Fiction, nonfiction, poetry—it doesn’t matter. If it’s a chapbook, I want to get my hands on it. Wordrunner eChapbooks offers a twist on the usual chapbook by bringing them online. Dedicating each of their issues to one writer, they create a digital chapbook, a great little showcase of one author’s work.

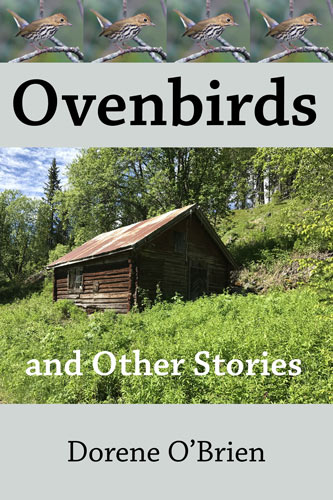

The Summer 2018 issue features Ovenbirds by Dorene O’Brien. The six stories give a digestible sample of fiction from the experienced, Detroit-based author.

In the chap’s titular story, O’Brien makes it known that she is not afraid to shine a light on the ugliness of everyday life and our interpersonal relationships. “Ovenbirds” finds the narrator living a quasi-normal life in with her daughter and firefighter husband, haunted by the past. Abducted from the mall as a teen and held captive by a serial killer in a cabin the mountains, the narrator, now physically free, has nightmares and graphic daytime fantasies of violently rescuing her daughter from the hands of men like her abductor. While the story is rife with tension, both in flashbacks and in the present day, the narrator does end reflecting on the things that keep her going:

I believe in the small things, the things I can live in one moment or hold in the small of my hand: the thin strand of hair over my daughter’s right ear, the stippled geranium pot on the kitchen window ledge, the strength of my husband’s callused hand as it hovers, gently, over my thigh.

The piece discusses trauma and its continuing aftershocks in a frank and straight forward way, the story pulling readers in and keeping us tense as we never know when we’ll be back in the cabin with the abductor. The story’s ending offers readers some peace with the knowledge that the narrator has found sources of comfort as she struggles to stay in control of her new life.

Also navigating family roles and ideas of comfort and control is “#12 Dagwood on Rye,” the story following the narrator after a car accident. At his wife’s urging, insisting she’s seeing concerning changes in his behavior and is concerned about his obsession with the sandwich he lost when he was hit by the car (a #12 Dagwood on Rye, of course, a recipe linked in the story for those feeling a little peckish after reading), he visits a doctor that he immediately views with contempt:

Dr. Michael wears blue jeans and canvas tennis shoes, and rather than the standard set of walnut-framed diplomas from Harvard or Johns Hopkins, his office bears blatant proof of his gross athleticism: tennis and lacrosse trophies, swimming medals, a plaque listing his name as captain of the rowing team. What’s he trying to prove?

On top of these tense and uncomfortable sessions which the narrator always leaves early as a way to feel some semblance of control, he’s put on medication that gives him dreams. In these, he encounters powerful men in history and has to make the decision on whether or not to show them up by being great at the tasks they present him. Does he strike out Fidel Castro playing baseball? Does he take the banjo Willie Nelson proffers and show off in front of a huge audience? Does he take control of his own destiny, or doesn’t he? Mixed with these dreams are the conflicted feelings of resenting his wife’s concern but wanting to be the husband she wants, the father his daughter deserves. But there’s a moment of realization that his wife’s new-found interest in his mental health “is her act of survival, her attempt to take control of her own life,” much like the dumping of his medication is his own attempt at the same. O’Brien makes us wonder just what we’ll put ourselves through before taking control of our own lives.

Or maybe it would be better to just have someone else take control for us. O’Brien explores this concept in “Wrong Number.” Connie finds herself trying to disappear into a bag of Skinny Pop in her mother’s house after her death. Jarred from her thoughts by the phone ringing, she is unable to hang up on the wrong number caller:

“Edie, please don’t hang up. Please. Just listen. I’m really, really sorry. You know you mean everything to me. You have to forgive me.”

Connie’s heart thumped in her chest. She had never been apologized to by anyone, let alone by a contrite man.

Staying on the line, Connie talks to the contrite man, assuming the role of Edie. As Edie—”Who was this woman? Connie wanted to know more about her, this person with compelling eyebrows who shared her feelings about sand worms”— she chides him for his mistakes and when he promises ways to win her back, she eggs him on, commanding: “Write me a poem.” Later she continues playing conductor to these strangers’ lives: “[B]uy some Pop Rocks and bring dinner to my place tomorrow night. Don’t talk about this phone call. If you bring it up I’ll act shocked, pretend it never happened. That’s how we start over.” Like “#12 Dagwood on Rye,” this story seems almost humorous on the surface (I bet we all know someone who’s trolled a wrong number caller or texter for some laughs), but there’s heartbreak in the story: Connie’s conflicted feelings about her mother after her death; her loneliness; her hunger to be treated well by a man, even a man she doesn’t know and will never meet; her desire to be a woman like Edie.

The three other stories in O’Brien’s Ovenbirds deal with the complex web of familial relationships. “Emma Reflected” looks at three siblings and their botched attempt to find meaning after their mother, Emma, is put into an assisted living facility when her dementia becomes too extreme to ignore. “The Good Daughter” focuses on Darlene as she sits beside her mother’s deathbed. Sarah, the “good daughter,” has not yet made it to the hospital and Darlene must decide if she should set aside her conflicted feelings toward her mother during her final moments. “Then I Snapped” is a dark examination of familial responsibility, the young narrator using the tools he has on hand as he does what he feels is necessary in order to deliver his little sister from the hands of their abusive father and the adults who fail to protect her.

Another fiction chapbook is on the way and will be published in December, so readers still have plenty of time to delve into the tough yet rewarding stories of Ovenbirds and sign up for the Wordrunner eChapbook newsletter before a new digital chapbook hits inboxes.

[www.echapbook.com]