I was fifteen-years-old when my brother enlisted in the Marine Corps and headed off to California for boot camp a few short weeks after his high school graduation. My cousin and then my aunt’s fiancé were the next to join, and before the three of them, it was my mother’s father and my great uncles. In a way, it has almost become a family affair to join the military, so reading online magazine Collateral Literary Journal felt like a welcoming and comforting experience—it is edited and filled with work by people who “get” the lifestyle. Each issue publishes voices from those touched by military service in poetry, prose, and art.

The fiction reads realistically, coming off almost as genuinely as nonfiction. “Homecoming” by E.M. Paulsen tackles the subject of PTSD when a soldier on leaves visits a laundromat and ends up frozen in fear when another patron’s child begins to choke on a cookie. Paulsen’s details put us in his shoes, stirring up the feelings of panic that can be triggered at any moment, even when you’re just innocently doing laundry.

After “The Ferry Back” by Morgan Crooks, Crooks reveals the fiction piece—featuring the complexities of a family relationship revolving around a military patch—”draws its conflict from personal experience: a war never truly ends, not within one lifetime or many.” Like Paulsen, Crooks writes with realism, the family interactions authentic.

With fiction so genuine and honest, one can expect the nonfiction to follow suit. Spoiler alert: it does. Kay Henry in “75 Years Later, What I Still Don’t Know” compares her life with her father’s seventy-five years earlier:

At 8:00 in the morning, I’m enjoying an ordinary breakfast outside on the front porch [ . . . ]. Except for a distant neighbor’s tractor, all is quiet.

Seventy-five years ago at this time of day, bombs began to fall on my father. Torpedoes began to hit his ship. [ . . . ] The U.S.S. Oklahoma, struck in the first minutes of the attack on Pearl Harbor, began to list. Young men began to die. My father was twenty-two.

She imagines him over and over, weaving between her life and his past: “Not to feel guilty or superior, nor to deepen my own sense of loss, but to see both days with more clarity. To know my young father. To bring him home.” By picturing this day and trying to put herself in his shoes, she is attempting to reach a greater understanding of the young man who experienced an incredible trauma, using writing to help achieve this.

Travis Burke utilizes a similar device in “Crawling Uphill,” the prose moving back and forth between present time in Portland and his past tour in Afghanistan. Burke repeatedly dreams of Massoud, an Afghan soldier friend who lost his life. Massoud and poppies haunt Burke, showing up again and again, in dreams and when awake. Massoud’s words stick with him: “An ant crawls uphill to go home.” And so Burke climbs a mountain as if climbing closer to home and the peace found there.

In “Dear Judith Wright” by Lisa Stice, the speaker wishes for peace for their daughter who keeps waking from nightmares, night after night. Stice gives her inspiration for the poem, explaining that she feels Judith Wright, who “wrote in support of the people with the least amount of power” would “empathize with the military children who are too young to really understand or express their feelings.” Stice’s speaker recycles Wright’s own words in an attempt to give some momentary peace and comfort: “it is only our past and future / troubling your sleep.” I remember my own nightmares from when I was a teen and my brother was overseas in Iraq. Much like the speaker’s child, I would wake up from dreams where I’d lose my brother in varying ways, unable to fully explain the fear and loss experienced in my dream world.

Tami Haaland’s “Noon Lockdown” is as timely as ever, especially after yesterday’s school walkouts protesting gun violence. A school is on lockdown, “men with guns / two floors down, swat teams, / nine police cars. We plan what to do.” Some students panic:

One is angry because

her mother failed to text love,

so I kiss her head as I would kiss

the heads of my own grown children.

The situation ends up being a misunderstanding. No one is in any real harm, and they’re all free to leave, the speaker visiting her own mother, “whose mind has turned / to lace.” The two sit together, the speaker not sharing the day’s events:

I hold her hand as if

there is nothing to say. [ . . . ]

I don’t

tell her a thing she will forget.

While the speaker offered comfort to her students when they needed it, she is left to quietly process on her own. Life goes on after the panic settles. Haaland has a new book coming out from Lost Horse Press next month: What Does Not Return. The distributor’s website says the collection “examines dementia and caregiving,” and if “Noon Lockdown” is any indication of the type of work one might find in the forthcoming book, it promises to be a thoughtful, skillfully written collection.

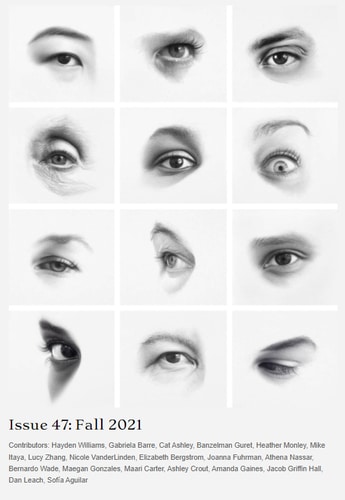

Art by Laura BenAmots accompanies the issue, pieces from “The Battle Portraits” collection staring out with emotive eyes. Readers can close out the issue with an interview with the artist along with full portraits from the series.

Collateral gives a personal, inside look into military and military-adjacent life. The journal offers community and comfort to those connected to military service, and for those living completely outside this lifestyle, Collateral still offers a welcoming, enlightening experience.

[www.collateraljournal.com]

Nonfiction Contest Winner

Nonfiction Contest Winner Every year, the

Every year, the  Journal of the Month

Journal of the Month

Join in

Join in If this data shared by

If this data shared by

Pittsburgh-based literary magazine

Pittsburgh-based literary magazine

Winner

Winner

First Place

First Place The Spring 2018 issue of

The Spring 2018 issue of

The HitchLit Review: A Secular Literary-Arts Journal

The HitchLit Review: A Secular Literary-Arts Journal The Winter 2017-2018 issue of

The Winter 2017-2018 issue of  The Editor’s Note in

The Editor’s Note in  Peter Nathaniel Malae [pictured] of McMinnville, Oregon, who wins $2500 for “El Camino.” His story will be published in Issue 103 of Glimmer Train Stories.

Peter Nathaniel Malae [pictured] of McMinnville, Oregon, who wins $2500 for “El Camino.” His story will be published in Issue 103 of Glimmer Train Stories. Twyckenham is a name linked strongly with South Bend and

Twyckenham is a name linked strongly with South Bend and  Autumn House Press annually hosts contests for full-length manuscripts of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Each winner receives publication, and $2,500 ($1,000 advance against royalties and $1,500 for travel and publicity). The 2017 winners will be available for purchase next month.

Autumn House Press annually hosts contests for full-length manuscripts of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Each winner receives publication, and $2,500 ($1,000 advance against royalties and $1,500 for travel and publicity). The 2017 winners will be available for purchase next month. Available this month is the winner of the 2017

Available this month is the winner of the 2017  1st place goes to Corey Flintoff [pictured] of Cheverly, Maryland, who wins $2000 for “Early Stages.” His story will be published in Issue 103 of Glimmer Train Stories. This will be his first major print publication.

1st place goes to Corey Flintoff [pictured] of Cheverly, Maryland, who wins $2000 for “Early Stages.” His story will be published in Issue 103 of Glimmer Train Stories. This will be his first major print publication.

The cover image by

The cover image by  Olives are a succulent fruit, each containing a seed with which to grow more nourishing deliciousness. What better inspiration, then, for

Olives are a succulent fruit, each containing a seed with which to grow more nourishing deliciousness. What better inspiration, then, for  Far Horizons Award for Short Fiction

Far Horizons Award for Short Fiction In her craft essay in the

In her craft essay in the