The word “museum” is usually associated with velvet ropes, alarms, roving guards. As Fanning introduces the word sudden into these carefully executed spaces filled with unfamiliar objects, he invites motion into a static world, redrawing the boundaries of artifact and observation. Though Our Sudden Museum is dedicated to the memory of his father, sister, and brother, and is filled with funny and painfully wrought elegies, unforeseen death reverberates his attention into new, unexpected places. Ultimately, with a broad range of forms and tones, Fanning ushers us into an elevated, enlightened space only reached through profound grief. Fanning’s delivery is charged with urgency and grace, since at any moment, the mundane or cherished could be taken away, suspended under glass.

While objects in museums travel and assume hefty historical weight through their membership in a rigid collection, Fanning tackles the transfiguration of emotion, the kinetics of memory. The book begins with “House of Childhood,” where, in a fluttering metamorphosis, the speaker is alternately a house, a bird, and the very seams holding artifact together:

Every dream I’m in its bones. Its bones

though hollow of me now. Its walls. What holds

the hallowed dust. The joists. The moans.

Oh Ghost, Oh Lady of Sorrows, I’m old.

I’m grown and gone. I’m a bird that can’t thrash free.

“The Bird in the Room” captures a similar dynamism that is quite original in a volume exploring grief. When faced with the challenge of listening to an aging parent, how many of us would invite such action, such ambiguity, into the scene?

As she speaks I try to hear her

through another feather

falls

from her mouth

The shadow of a wavering tree

covers the wall

Does she know

it’s in the room with us

In a volume chock full of confrontations with death, this speaker copes how most of us would:

What are you doing she asks

as I open

her door trying to let

the thought of her

death escape me

And yet throughout the book, we are offered the full gamut of methods of weathering death, and Fanning isn’t afraid of delving into sometimes vulgar or vividly morbid detail.

“I’d kick your coffin over / and piss the makeup off / your face, my sister says,” begins “Love Poem,” which catalogs the ultimately ineffective threats siblings hurled to keep a suicidal brother alive:

One week ago tonight, we stood over Tom

in his box, staring at his bad

cosmetic job, rouge on the flat

cheekbones, the lips sealed

a sick pink.

And yet the magic of Fanning’s work lies in the universal. Even if the reader hasn’t experienced the death of a sibling, who hasn’t joyfully perused items that don’t belong to us? “Sister, now I can tell you this: / how I’d steal // into your room / days you were gone,” begins the relatable “Flute.” The poem contains a breathtaking turn common in Fanning’s work:

I’d stare at the disassembled parts:

each silver tube snug in red

velvet, click of fingered keys

rubbed bronze.

I lacked the adequate prayer

my lips might blow across you,

kneeling over your open casket.

While the book is not broken into sections, the sequencing of poems slowly progresses toward the birth and rearing of children by the end, which provides a perfect counterpoint to such profound loss. In “Paper Dolls,” Fanning masterfully renders the joy and fear involved in an impending birth:

Since our news, the hours

wobble like bubbles from a playground

wand, every minute drifting, oblong

and sure to burst.

And what do children do but rewrite any conception of time we might have had before them? In “Saving the Day,” Fanning’s poetic imagination turns our orderly, painful adult world on its head when he shares discoveries “Upon finding my lost day planner on the floor of my daughter Magdalena June, age 2“:

Pages of my hours’

rigid grids splashed with your unruly hues,

my walls of stacked blank days splattered

by spilled giggles and curlicues. Sweet girl,

my year’s unwound by your fluttering hands.

With my future made so bright by you,

may I ever be ready for never.

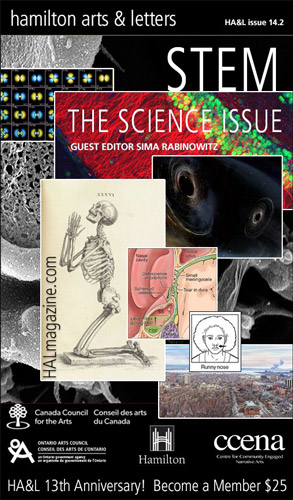

The cover image of the fall 2017 issue of

The cover image of the fall 2017 issue of  Tim L. Vasquez of Untamed Photography offers a seemingly surreal image for the cover of the fall/winter 2017

Tim L. Vasquez of Untamed Photography offers a seemingly surreal image for the cover of the fall/winter 2017  Speculative Fiction in Translation (SFT) “often flies under the radar, despite the fact that it is an important part of the speculative fiction universe,” writes author and editor Rachel Cordasco in her introduction to a special section of “

Speculative Fiction in Translation (SFT) “often flies under the radar, despite the fact that it is an important part of the speculative fiction universe,” writes author and editor Rachel Cordasco in her introduction to a special section of “ The December 2017 issue of

The December 2017 issue of  It’s hard to get the full effect of the Fall 2017

It’s hard to get the full effect of the Fall 2017

Love love love

Love love love  The Autumn 2017 issue of

The Autumn 2017 issue of  Katie M. Flynn’s “

Katie M. Flynn’s “ The Fall 2017

The Fall 2017  Billy Renkl’s “Watching the Sky #2” collage of antique British chromoolithographs is the cover art for v32 n2 of

Billy Renkl’s “Watching the Sky #2” collage of antique British chromoolithographs is the cover art for v32 n2 of  The front cover of Fall/Winter 2017

The front cover of Fall/Winter 2017  The Winter 2017 issue of

The Winter 2017 issue of  The

The  Publishing since 1967 from the University of Victoria,

Publishing since 1967 from the University of Victoria,  The Indianapolis Review

The Indianapolis Review The University of Iowa Press published the winners of the 2017 Iowa Short Fiction Award and the 2017 John Simmons Short Fiction Award last month.

The University of Iowa Press published the winners of the 2017 Iowa Short Fiction Award and the 2017 John Simmons Short Fiction Award last month. 1st place goes to Chase Burke of Tuscaloosa, AL [pictured], who wins $2000 for “That’s That.” His story will be published in Issue 101 of Glimmer Train Stories. This will be his first major print publication.

1st place goes to Chase Burke of Tuscaloosa, AL [pictured], who wins $2000 for “That’s That.” His story will be published in Issue 101 of Glimmer Train Stories. This will be his first major print publication. Edited and published by Richard Peabody, along with the work of Associate Editor Lucinda Ebersole,

Edited and published by Richard Peabody, along with the work of Associate Editor Lucinda Ebersole,  In her Editor’s Notes to Issue 13 of

In her Editor’s Notes to Issue 13 of  In her last notes, when her hand began

In her last notes, when her hand began “Twenty years ago,” writes Brevity Editor Dinty W. Moore, “I had an idea for a magazine that combined the swift impact of flash fiction with the true storytelling of memoir, and

“Twenty years ago,” writes Brevity Editor Dinty W. Moore, “I had an idea for a magazine that combined the swift impact of flash fiction with the true storytelling of memoir, and  After publishing 12 print issues from 2004-2015 in association with Columbia College Chicago, and a brief hiatus,

After publishing 12 print issues from 2004-2015 in association with Columbia College Chicago, and a brief hiatus,  First place: Arianna Reiche, of London, England, wins $3000 for “Archive Warden.” Her story will be published in Issue 101 of Glimmer Train Stories. [Photo Credit: Laura Gallant.]

First place: Arianna Reiche, of London, England, wins $3000 for “Archive Warden.” Her story will be published in Issue 101 of Glimmer Train Stories. [Photo Credit: Laura Gallant.]  The fall issue of

The fall issue of  Catherine Heard’s work can be found on the cover of

Catherine Heard’s work can be found on the cover of  The

The