“Slow” is the theme of the most recent issue of North Dakota Quarterly (v80.2). In their introduction, guest editors Rebecca Rozelle-Stone and William Caraher discuss the “wide range of experiences that fall under that heading,” including slow as “a romanticized glorification of a supposedly ‘simpler,’ more thoughtful and more deliberate past, engaging concepts like Paul Virilio’s “picnolepsy,” the digital “information age,” Nietzsche and existential anxiety, and how the slow movement has expanded “to embody a popular interest in slowing down the pace of modern life.”

We have created both a celebration and a pedagogy of slowness in our lives, the editors write, and Anne Kelsch’s essay on the Slow Teaching movement “attempts to balance the conscientious and deliberate pace of craft against the industrial expectations of the modern university.” With the many battles I face daily on my own work front in higher education, and no doubt more to come with “free college,” I was drawn to Kelsch’s essay, hoping for some wizened argument from which to draw my next round of ammunition. War and Slow seem to be the two metaphors at work here, while the philosophy of modern education, and the whole concept of the liberal arts education that have come under scrutiny.

The university, like the two-year college, if not feeling already, soon will: How quickly and cheaply can you “educate” students to prepare them for a good-paying job? In essence, the college education is being replaced by job training. “Free College” will only be free as long as every credit counts toward graduation (and a job) and with fewer and fewer credits (I’ve recently learned the 62 previously allowed for federally funded two-year graduation will be dropping to 60).

This year, I continue a six-year-long fight with an administration that wants to see our four-hour Composition I class reduced to three hours, despite the fact that students are coming in less prepared and the fact that our state college-to-university transfer agreement now only requires one semester of composition instead of two (a total of four hours instead of seven, and now administration wants three instead of seven, all in the name of fiscal responsibility to our stakeholders – sound familiar?). One administrator argued that if we can’t have the same success in fewer hours, then we’re not very good teachers.

Seriously. We need to Slow. This. Down.

In her essay “Slow Teaching: Where the Mindful and the Modern Meet,” Anne Kelsch writes of that introductory level classes are “typically crammed with an overwhelming range of content” and students do not see this “formal learning” as equating to “wisdom.” And now we are being told to do even more with less. Kelsch draws connections with Romanticism and the Slow Movement: “Both intend to mitigate the negative effects of that change and to mold the human response to it. Both seek to restore a sense of wholeness to the human condition by recapturing what is being lost.”

Kelsch draws from a number of educators, writers, and theorists in her essay: Mark Bauerlein, Geir Berthelse, Tara Brabazon, Nicholas Carr, L. Dee Fink, Bruce Hammond, Jim Hold, Carl Honore, Bob Cole and Jennifer Russell and many more. She explores the thread of Slow Learning and technology and high-impact practices.

One profound connection Kelsch makes is between George Kuh and Chun-Mei Zhao’s research on learning communities that found “When faculty and institutions intentionally foster engagement, ‘the learning is deeper, more personally relevant and becomes part of who the student is, not something the students has'” and Daniel Chambliss’s and Christopher Takacs’s study, How College Works, in which “they concluded that personal relationships with professors and peers were decisive in determining collegiate success. Their research established that a positive relationship with even one faculty member has a profound impact.”

Slow Teaching addresses sustainability, Kelsch writes, “both in having students value it as a goal and in terms of sustaining life-long learning, rather than just producing graduates. Ultimately, Slow Teaching implies a critique of our current system of credits and degrees with its focus on what students have passed rather than what they have learned.”

Keslch then quotes Tara Brabazon: “Simply because a curriculum is compressed into semesters, passed through validation protocols, squeezed into subject benchmark templates and signed off through show-trial external examination boards does not mean that life-changing education has been created.”

But, what good is all that learning if it doesn’t get someone a job? That’s the line I hear in my everyday. Especially if the government is paying for it, since a good percentage of our students are Pell Grant recipients. Free College may sound great on the surface, but scratch that, and I think what we’ll see is the start of two distinct tiers of education. Job Training and Higher Education that aims to educate the Whole Person, as Kelsch says the Slow movement will do, with a “genuine desire that students learn in ways that are more meaningful and enjoyable. . . striving to ensure. . . students get what they need in order to live more fulfilled lives.”

Like in so many facets of our culture, I fear that this may be a reaffirmation of the Matthew Prinicple, a continuation of some-will-have and some-will-have-not. Which leaves us teachers as it always has, fighting for what we know is right against all fiscal odds.

Cambodian Invisibility in Education by Christina Nhek is the most recent in the What’s Your Normal series, a regular feature on the Asian Pacific American Librarians Association website. Nhek writes, “I came to understand that I fell into the stereotypes that are associated with mainstream Asian Americans. My family came to the U.S. to give their children better opportunities. I had an educational standard I adhered to because of the expectations of my parents. I needed to succeed. What I failed to recognize, however, is the fact that as Cambodian American, I am not part of mainstream Asian American communities.”

Cambodian Invisibility in Education by Christina Nhek is the most recent in the What’s Your Normal series, a regular feature on the Asian Pacific American Librarians Association website. Nhek writes, “I came to understand that I fell into the stereotypes that are associated with mainstream Asian Americans. My family came to the U.S. to give their children better opportunities. I had an educational standard I adhered to because of the expectations of my parents. I needed to succeed. What I failed to recognize, however, is the fact that as Cambodian American, I am not part of mainstream Asian American communities.”

Since its inception in 2011,

Since its inception in 2011,

The Boxcar Poetry

The Boxcar Poetry

The

The

In case you missed it featured in the Editor’s Picks of the February

In case you missed it featured in the Editor’s Picks of the February  Barking Sycamores

Barking Sycamores The new free ebook from Argotist Ebooks is

The new free ebook from Argotist Ebooks is  The

The  The poems in

The poems in  Mudfish

Mudfish Barely South Review 2015 Craft Issue

Barely South Review 2015 Craft Issue World’s Best Short-Short Story Contest

World’s Best Short-Short Story Contest

Black Lawrence Press runs their

Black Lawrence Press runs their

Angie Estes, an Ashland University faculty member in the low residency Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program, has won the $100,000

Angie Estes, an Ashland University faculty member in the low residency Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing program, has won the $100,000  A decision to proclaim 21 March as World Poetry Day was adopted during UNESCO’s 30th session held in Paris in 1999. In celebrating

A decision to proclaim 21 March as World Poetry Day was adopted during UNESCO’s 30th session held in Paris in 1999. In celebrating  Free Verse Editions, the poetry series of Parlor Press, hosts

Free Verse Editions, the poetry series of Parlor Press, hosts  Fiction judge Sean Bernard selected Matthew Di Paoli [pictured] of New York, NY, who wins $250 for “Sweeping Glass.” His stories have appeared in multiple journals, and he currently teaches at Monroe College.

Fiction judge Sean Bernard selected Matthew Di Paoli [pictured] of New York, NY, who wins $250 for “Sweeping Glass.” His stories have appeared in multiple journals, and he currently teaches at Monroe College.

Daniel Torday, Director of Creative Writing at Bryn Mawr College, shares his insight

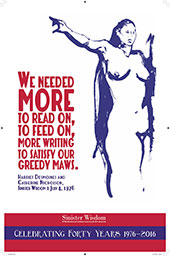

Daniel Torday, Director of Creative Writing at Bryn Mawr College, shares his insight  To celebrate its upcoming 40th anniversary,

To celebrate its upcoming 40th anniversary,  Now in its second issue,

Now in its second issue,