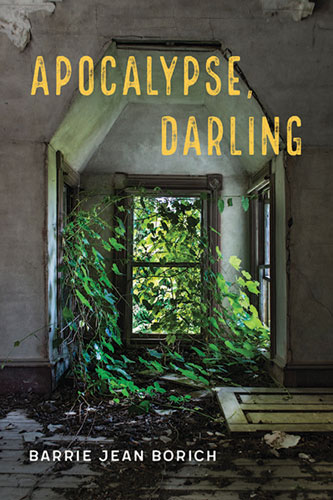

Apocalypse, Darling

Unfamiliar with Barrie Jean Borich’s previous works, I decided to forgo my usual research concerning the author’s expertise and dive into reading Apocalypse, Darling right away. Peeking inside just to get a taste of her writing, I suddenly found myself unable to stop reading despite my previous plans for the evening. Just like the author, “I almost forget we have some place to be,” so I cancelled my plans to explore Borich’s world of “the beautiful wastelands.”

Unfamiliar with Barrie Jean Borich’s previous works, I decided to forgo my usual research concerning the author’s expertise and dive into reading Apocalypse, Darling right away. Peeking inside just to get a taste of her writing, I suddenly found myself unable to stop reading despite my previous plans for the evening. Just like the author, “I almost forget we have some place to be,” so I cancelled my plans to explore Borich’s world of “the beautiful wastelands.”

“What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow / Out of this stony rubbish?” An epigraph placed above the photo of a desolate landscape, an industrial forest of structures looming above the frozen swells of the lake, opens up this collection of nonfiction essays. Borich notes that “in this work, [she] borrowed from and expanded upon the language, tone, and structure of T.S. Elliot’s long-poem sequence The Waste Land.” While this poem has impacted works of many authors, Borich offers a unique perspective on the familiar poem as she explores bodies, relationships, and love in connection to the wasteland.

Separated into five parts and multiple chapters, the book appears to be a collection of fragments which include Borich’s memories, reflections, and stories about herself, her spouse Linnea, and her family. The timeline of the essays is non-linear, contributing to the idea of fragmentation and episodic character of the events that range from the 1950s to present.

“Wasteland Oasis” opens up the first part of the book with a startling image of an “oasis:”

An expanding patch of unnatural green. Neon green. Denial-of-impending-annihilation green. An over-bright amoeba, surrounded by the stacks of Northwest Indiana. Windowless steel mills, smoke spume, ground that appears as if the skin has been scraped away, a rusty, gouged tableau, wasteland gray interrupted by the peacock blue painted exterior of U.S. Steel Gary Works—as if someone in charge had consulted with a home decorating guru. Shall we try blue, Darling? Costume-party, feather-boa blue? Blue to accent these badlands that would stretch all the way to forever, except for the khaki bumper of Lake Michigan.

Starting with such a devastating image, Borich caught me off-guard with her witty remarks about the blue color that appears to be completely out of place. As if “decorating” images of the wasteland, this witty tone underscores the seriousness of the problem.

Connecting all the essays, the story centers on Borich and her spouse attending a wedding:

This decimated plain, punctured by the green of the golf course, is where my father-in-law, age seventy-five, is about to wed his long-lost, newly found, pinkly smiling, high school sweetheart, in the presence of middle-aged children who would not exist if this father, and this mother, had married each other the first time they were in love.

While the central idea appears to be simple and straightforward, it is important to note the beautiful complexity of the book as it not only intertwines present with past, but also illuminates intricate connections between people and the land.

In the essay titled “His Not Daughter,” Borich expands on the character of her father-in-law and the relationship he has with his daughter Linnea, Borich’s partner:

It’s his unblinking conservatism which keeps him from full knowledge of all his children but which, in the case of Linnea, takes the form of dismissive homophobia. Genderqueer and male-expressive Linnea, who only wincingly accepts the pronoun “she,” is far from a closet case, so her father’s dismissal means he’s missed a great deal.

Despite this cold relationship with the father of the family, Borich and Linnea decide to come to his wedding.

As Borich reveals the few interactions she has had with her father-in-law, she wonders if it is possible for him to change and accept both his daughter and her partner. “What will it take to bring a wasteland back to bloom?” asks Borich as she connects the desolate landscape to the character of the father. “The Cruelest Month” draws the parallel between the regeneration of the landscape and love. Is it possible for love to revive “the wasteland” of the soul? “Is love [ . . . ] an accident, a decision, or just an arrangement we make with hope?”

In addition to the exploration of the familial relationships of her father-in-law, Borich traces the change in the industrial landscape of her own hometown. In place of “a rubbish of dead fish littering the wake of the waves,” she finds the clean place: “a habitat that speaks to the erotic charge of life. The old dunes that were dying are now living.” Borich reflects on the idea of change in both the landscape and a person’s character, “I want to see if change is possible, if wastelands can revive, if lost love and re-found love can coexist, if unloving fathers can become loving, even lovable?”

In her essays, Borich reflects on various themes including love, identity and its construction, and familial relationships. The author also brings readers’ attention to the desolate industrial landscapes, particularly, “the Calumet Region [which] has often been included on lists of the worst environmental disaster areas on earth.”

Finishing this book in one sitting, I was left to wonder about my own relationships and “wastelands” that formed me as a person. Can we change? Can we revive what was once peaceful and beautiful? Barrie Jean Borich’s Apocalypse, Darling is a deep and complex work that allows readers not only to get a glimpse into the author’s life but also reflect on their own.